Historic Burial Sites in the Districts

The core of the Surinamese economy was formed by the plantations until well into the nineteenth century. The plantation was the production unit, but also the social unit: an autonomous community of between 50 and 500 people. The owner and his family lived there, and then there was the free staff, consisting of director, supervisors and sometimes craftsmen. But the vast majority of the community were enslaved people. All of them were buried on the plantation. The owner and director in a small, distinguished cemetery near the plantation house, the enslaved in a simple cemetery near the edge of the plantation. It is not known where the free personnel were buried.

Remains of burial sites

Most of the plantations have long since been abandoned, and the forest has reclaimed its rightful position. The wooden headstones have perished, and of the cemeteries in general nothing remains. Only deviating vegetation, such as hangalampoe (ed.: Chinese rose), suggests that there was once a cemetery there. Only the rich tombstones of the owners can now and then be found. They were ordered in Europe, and placed on the grave a few years later. If we combine the data on it with the old church registers, the story of the plantation takes shape. Such as the tombstone of Johanna van der Meulen, who died in 1743. It is located in the lonely woods along the Pericakreek. If we check her records, it appears that she was the owner of the rich sugar plantation Poelwijk, and the distant place where she is buried was once the busy centre of that plantation.

Most headstones have a default text. Name, date of birth and death are stated, that's all. Only occasionally is there a personal message, such as on the stone of Charles Paul Bennelle de la Jaille on Nieuwzorg (ed.: also called 'Nieuw Sorgh'). “Murdered in single combat”, reads the epitaph. The Nieuwzorg plantation has long since been closed, but the place has remained inhabited, and the story of the duel has been handed down orally. The locals on Nieuwzorg still tell something about a deadly quarrel between two brothers, who were both in love with the same enslaved young woman. The girl was executed after the unfortunate outcome.... The story has naturally expanded over time.

Directors cemetery at Marienburg (photo Philip Dikland, 2001).

Directors cemetery at Marienburg (photo Philip Dikland, 2001).

On the plantations that are still in use, the old grave sites are kept reasonably well. At the back of the plantation on Marienburg is the director's cemetery, with thirteen funerary monuments shaded by beautiful old trees. At Rust-en-Werk, the old cemetery of the Crommelin family is now in a meadow, but this was once the backyard of the large house. The graveyard is maintained and has been cordoned off so that the cows stay outside. The plantation has a second burial site from the nineteenth century.

The tombs on the plantations in Nickerie are a special case. There are three remaining, two on Plantation Paradise, and one on Plantation Waterloo. But the text plates of all three on the funerary monuments have been chiseled away. By relatives from Scotland, locals say, they came one day and took the plates with them. A peculiar story.

Research on Plantation Waterloo. The grave was once broken into and the nameplate removed. (photo Jan de Bruin, 2003)

Research on Plantation Waterloo. The grave was once broken into and the nameplate removed. (photo Jan de Bruin, 2003)

Funerary monuments tell a story

Sometimes the funerary monuments recall historical events. The Dutch farmers who emigrated to Saramacca in 1845 were half wiped out by typhus within months. They were buried in Groningen, but the wooden headstones on their graves have long since disappeared. Only the stone funerary monument for Anna Sophia Pannekoek, wife of the pastor who led the disastrous settlement attempt, still dates from that time. She was one of many who died in 1845. The cross street opposite the cemetery is called Pannekoekstraat, in her memory. But that memory has faded. The youth of Groningen think that the Pannekoekstraat is named after the old bakery in the middle of the street. He would occasionally have made pancakes.

On Batavia we find the grave plaque of Anthon Johannes Cateau van Rosevelt, 22 years young. He is the son of Adriaan Francois Cateau van Rosevelt, an outstanding geographer and constructor, the architect of 's Lands hospital, among others. He could not prevent the early death of his son. Anthon was infected with leprosy, and there was no cure for it at that time. By law he was secluded in the leprosy hospital in Batavia, to spend the rest of his life there.

Jodensavanne

The Jewish planters were not buried on their plantation. Already in the seventeenth century they had founded their own centre in the middle of their plantations, the Jodensavanne. There are two cemeteries nearby, at Jodensavanne itself and at Cassipora. These remained in use until the end of the eighteenth century. They are still in good condition. Their tombs are richly decorated with Jewish symbolic images, just like in Paramaribo.

The Jewish planters fought a brutal war with the maroons. Brave and unyielding people on both sides, convinced of their own right. David Monsanto's tombstone is a reminder of that. He was buried in the cemetery of Jodensavanne in 1739:

Do Yncurtado Mancebo

David Rods Monsanto que foy

Matado

Por Os Crueys Negros

Alevantados Em 29 Menahem A' 5499

que corresponde

A 4 Sett'ro Ao 1739

SUA SANGRE SEJA

VINGADA

Translated (red.): From the courteous young man / David Rodrigues Mosanto who was / slain / by the cruel rebellious negroes / on the 29th Menahem of the year 5499 / corresponding to / the 4th September Ao 1739 / HIS BLOOD SHALL BE AVENGED.

Other stones also tell the same story of revenge and retaliation. Is the story of the other side also known? In Cassipora cemetery we find the tombstone of Sara de la Parra, who died peacefully in the year 1759 at the age of 66 years. Her good qualities are praised on the tombstone: her virtue, her justice, and her generosity. The angel of peace will welcome her at the gates of heaven. But the tombstone doesn't tell the full story. Sarah's justice did not extend to her enslaved. The Maroon captain Quakoe, one of the sixteen Aucan chiefs who would later make peace with the Dutch rulers in 1760, was an escaped enslaved from Sara's plantation. He was questioned a few months before Sara's death; he related that she had tortured him for many years, though he had benefited her for just as many years. Nevertheless, she wanted to "cut off his nose and ears until recomp(ensation)". Since he liked his appearance, he ran. In revenge he had made five (failed) attempts to get hold of her. But in order not to spoil the chance for peace, he would now refrain from further attacks. "I've missed her five times now, let her live now too" (Dragtenstein 2002, p. 189).

District Churches

The free colored population may have been partly buried on the plantations, but were often buried in the modest graveyards next to the small district churches. By law, every liberated person was obliged to choose a religion, and so they had the right to be buried next to the church of their choice. In Coronie, for example, we find small intimate cemeteries with nineteenth and twentieth century funerary monuments near all churches. Only in Totness and Friendship, the core of the district, are the cemeteries larger.

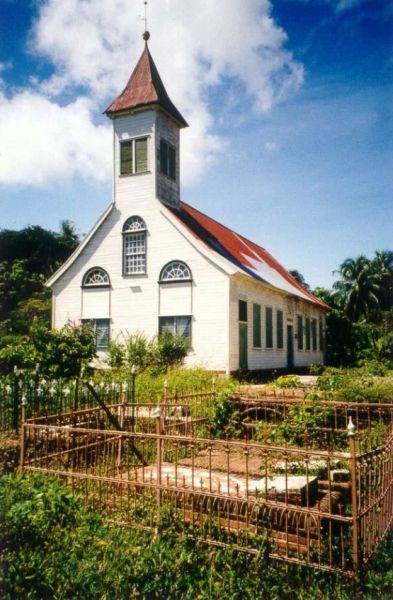

Moravian Church cemetery at Plantation Clyde in Coronie

Moravian Church cemetery at Plantation Clyde in Coronie

(photo KDV architects, 2000)

Nieuw-Nickerie is the second largest town in Suriname after Paramaribo. The village was established in 1870 between the plantations Margarethenburg and Waterloo on the Nickerie River, after the earlier village of Nieuw-Rotterdam, founded in 1801 on the coast, was slowly occupied by the sea. The old cemetery of Nieuw-Nickerie has been cleared, there is nothing left of it. There is only one old headstone in New Nickerie. This is located near the reformed church and dates from 1835 and was therefore taken from Nieuw-Rotterdam to Nieuw-Nickerie.

A separate chapter is formed by the plantations in Para, which after the emancipation were mostly bought over by the population consisting of former enslaved people. It had previously been eight timber plantations, where their ancestors had lived and worked in relative freedom. The connection to the land was greater than in the production plantations with their often inhumane regimes. So in Para there is continuous habitation from the time of slavery to the present day. It may be assumed that there is also continuity in burial customs. We see cemeteries not far from the residential core, with wooden headstones with round or heart-shaped tops. It was probably the same in the slavery times.

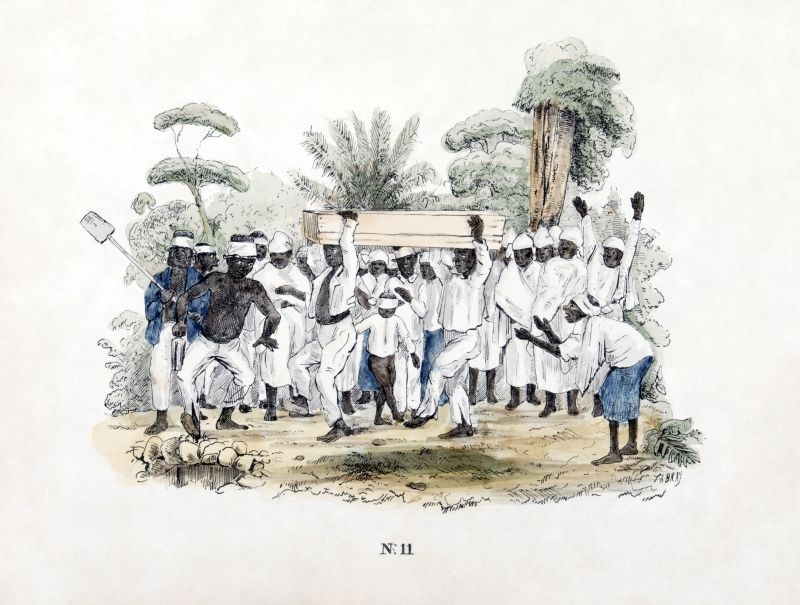

The manner of burial is depicted in a print by Bray from 1850. We see the coffin with the bearers walking in the same unpredictable stride as is still used in Creole funerals. The pass was purposely unpredictable to distract the spirits beyond the coffin, so that the dead would rest in peace.

'Funeral at Plantation' by Theodore Bray, 1850 (Royal Tropical Institute)

'Funeral at Plantation' by Theodore Bray, 1850 (Royal Tropical Institute)

In the time of the indentured servants, new funeral customs appeared. The Hindus cremated their dead, a new practice for Suriname that is increasingly being followed. The Javanese buried their dead, and protected them from the sun with oriental elegance by placing a parasol on the grave at the funeral, later replaced by a complete small house. Most of the plantation cemeteries have long since disappeared, but the custom is still alive in the newer cemeteries in the districts.

The future

Are the historical grave sites under threat? If they are tracked, no. The cemeteries in Coronie are occasionally cleaned, and in 2006 all were in reasonable condition. But if they are neglected, the power of nature soon becomes apparent. Trees grow up between the graves, destroying the tombs with their roots. The epitaphs are slowly fading due to erosion caused by rainwater. Still, they are usually quite readable and the genealogical information can be included. Protecting the loose graves in the woods is completely impossible. Nature is here on the one hand the destroyer, but on the other hand a good protector against human destructiveness: the graves are almost impossible to find. They lie under a carpet of leaves, and cannot be discovered without a guide. It is unknown how many there are, and how many have disappeared. Vandalism occasionally occurs, such as at the grave monument of Anna Maria Taunay on plantation “het Vertrouwen”. Located near the river due to land erosion, and was opened by fishermen to a supposed treasure inside.

Header: Cemetery Nickerie, outside Nieuw Rotterdam around 1860.

- Last updated on .