Introduction

The first encounter of Dutch sailors with the country that is now called the United States in 1609, was nothing short of a disappointment. On board with a mixed English and Dutch crew, they saw the hope of a passage to the riches of Asia obstructed by land. This land was inhabited but relatively empty and seemed fertile. In the following years, the new country was further mapped out and seemed to yield promising riches, including fur. The country was soon called New Netherlands.

Articles

- {articles category="226"}

- [link][title][/link] {/articles}

Dutch colony

After a few occasional winterings, several trading companies from Amsterdam decided to establish posts to trade more permanently with the residents. In 1613, fort Nassau was founded on an island in the Hudson near present-day Albany. Four years later, the post was abandoned again due to the difficult circumstances. In 1624, near the old fort a new fort was built by the Dutch West India Company (WIC). That company was mainly founded for trade with America and Africa. Now more posts and forts were founded including one on the ‘Noten Eylant’, later called Governors Island near the entrance of the Hudson. It was mainly Dutch and French speaking Walloon families who were the first to settle here and later spread throughout the area.[1] In 1626, the large island of Manhattan was bought by the WIC and the habitation moved to a fort on the southern tip of that island, called Amsterdam. Due to tensions in the area between the original inhabitants themselves and due to threats from other European countries, the fort attracted more and more people who felt relatively safe here. The settlement grew and was given the name New Amsterdam.

Detail of a watercolour by Johannes Vingboons from ca. 1665 that gives an impression of the city of New Amsterdam.

Detail of a watercolour by Johannes Vingboons from ca. 1665 that gives an impression of the city of New Amsterdam.

Nothing is known about the deaths that occurred during the first discoveries in New Netherlands. The forts that were built at the time were probably too small to bury the dead within the walls. In any case, it is known that the first formal cemetery at fort Oranje was founded in 1626. But it is known from those years that for those who fell in conflicts with the local inhabitants, a grave was often dug on the spot[2]. In New Amsterdam, a cemetery was formally built in 1628 near the church that stood north of the fort.[3] Little is known about grave monuments on those first cemeteries. The cemetery in New Amsterdam was described in 1656 as the old cemetery that was in very poor condition.[4] Not long after, a new cemetery was taken into use in New Amsterdam[5]. That cemetery has also largely disappeared because on the spot the English built a large church in 1698 with a completely new cemetery. As the Dutch colony expanded, churches with cemeteries all around arose near the villages. Villages such as Vlissingen, Breukelen and 's-Gravesande had their own cemetery early on. Further along the Hudson, more and more places with their own cemetery were created. Those who lived too far away from such a church often buried the dead at home. It is known that many family plots could be found near farms in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.[6]

Not only Dutch people lived in the New Netherlands. Attracted by the relative freedom of belief and the possibilities of purchasing large tracts of land, German, English and Scandinavian families also sought refuge here. They founded small communities, each with a church and its own cemetery. What they had in common was that the first burial culture was quite sober. While the oldest funerary monuments along the Hudson valley were often nothing else than a piece of fieldstone with inscription, in the English colony of Massachusetts a burial culture of sandstone stelae with elaborate symbolism developed. This was mainly due to the fact that there were more stonemasons and craftsmanship present than in the Dutch colony. Of course, wooden markers were also placed on the graves, but few of these specimens have endured time.[7] Certainly not in originally Dutch cemeteries.

The development of funerary monuments

The oldest still present grave markers on the cemeteries founded by the Dutch show examples of pieces of fieldstone with simple initials or short texts. Examples of this type of marker can still be found everywhere in the Hudson Valley and in present-day New Jersey. The idea of an eternal grave was very important to the small communities. That is why the development of the burial culture from the beginning of the eighteenth century is still visible in many cemeteries. In larger cities such as New York and Albany, the oldest cemeteries have long since disappeared, but in other places including Kingston and some former villages on Long Island there is still much to see. There, some cemeteries did not stop using the cemetery until the twentieth century, making three centuries of burial culture visible. The development of the use of the Dutch language in all its facets to the use of only English on the tombstones is also visible. On the oldest field stones, we often find only initials, a short family name and a year. Later more text comes into use where the spelling often differed. In particular de salutation was quite different: ‘hier leyt, hier leight, hier licht, hier liegt, hier lyt, hier lyt, hier lydt, hier leght’. At the end of the eighteenth century, the English "here lies" would increasingly supplant the Dutch words. Even later we find more modern texts such as 'In memory of' or 'to the memory of'.

In the cemetery of Flatbush, formerly called Midwout or Vlackebos, there are many stelae with Dutch text variations of 'Here lies'. (Photo Leon Bok)

In the cemetery of Flatbush, formerly called Midwout or Vlackebos, there are many stelae with Dutch text variations of 'Here lies'. (Photo Leon Bok)

The transition from the simple field stones went silently to the brown sandstone that was popular in the English colony with often a winged angel's head on top. Such expressions can still be found everywhere in older cemeteries. The oldest date from the end of the seventeenth century. In the nineteenth century, a white limestone came into vogue that, however, in many cases was even worse in quality than the brown sandstone. The text on the sandstone remained very sharp for a long time, but the stone tended to separate parts as if it were a skin. Especially when it came to lesser quality stone, often little remained. In the cemeteries you can see countless ways in which people wanted to preserve the stone, for example by applying metal covers. The white limestone was so sensitive to wind and weather that the texts often completely faded. At the end of the nineteenth century, granite was increasingly used, and experiments were also carried out with materials such as zinc. In the end granite won out over all other materials, but then on the tombstones, except sometimes the name, dutch texts were no longer in vogue.

The United States today

Many of the oldest cemeteries founded by the Dutch have disappeared. However, if you visit the villages and towns along the Hudson, you will soon find out that a lot has also been preserved. The graveyards of Sleepy Hollow and Kingston are worth a visit, but the ones in Brooklyn also give a good idea of how the Dutch fared.

The oldest cemeteries of Albany have completely disappeared. The headstones have been transferred to the current Rural Cemetery, far outside the city. (Photo Leon Bok)

The oldest cemeteries of Albany have completely disappeared. The headstones have been transferred to the current Rural Cemetery, far outside the city. (Photo Leon Bok)

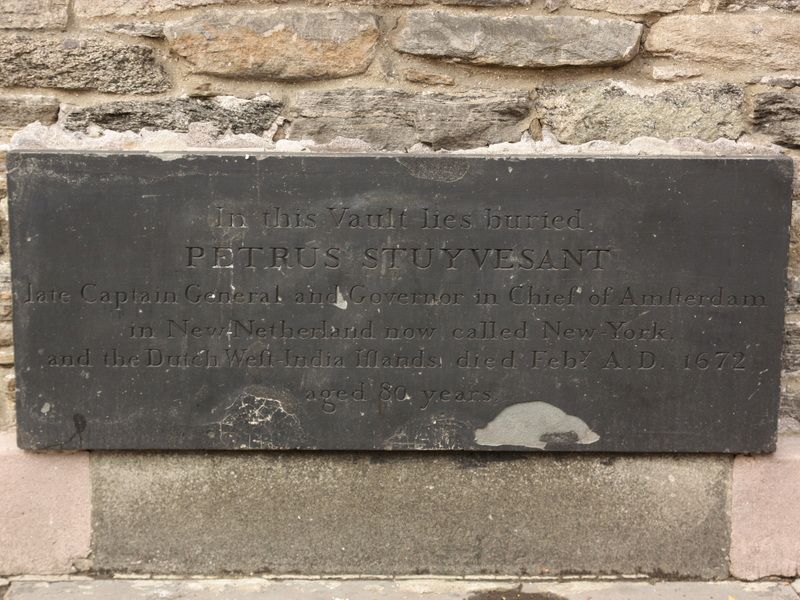

Most cemeteries are still in the hands of The Reformed Church in America (RCA), also called the Dutch Reformed Church, because the church fell under the Dutch Reformed Church until well into the eighteenth century[8]. The American church was founded in 1628 in New Amsterdam and then fell under the classis of Amsterdam. These churches preached in Dutch for a long time, but eventually from 1764 onwards English became more and more the main language. If you look at the distribution of cemeteries founded by the Dutch today, we will find them mainly in the valley of the Hudson, on Manhattan, the east side of Long Island and in parts of New Jersey. Some cemeteries fell into disuse early on but were preserved. Others disappeared to make way for buildings, such as the old cemeteries of Brooklyn and Albany. In those cases, the funerary monuments were kept and transferred to other cemeteries. For example, a large number of funerary monuments of the Brooklyn cemetery, dating from 1646, are now located in the nineteenth-century "Greenwood Cemetery". There they were transferred to in 1865 after the city of New York in 1849 had issued a ban on burial within the built-up area. The church on the spot had already been demolished in 1807 after a new one had been built more westwards. At the same time, the remains of an old Dutch cemetery, namely that of St. Mark's in the Bowery Churchyard were transferred to Evergreen Cemetery. St. Mark's was founded on the ground near the chapel that Governor Stuyvesant had built here in 1660. Nowadays we only find the tomb of Stuyvesant at the abandoned churchyard.

One of the oldest memories of a Dutch burial is that of Peter Stuyvesant, whose vault can be found under the church of St. Mark's in the Bowery in Manhattan. (Photo Leon Bok)

One of the oldest memories of a Dutch burial is that of Peter Stuyvesant, whose vault can be found under the church of St. Mark's in the Bowery in Manhattan. (Photo Leon Bok)

All in all, there are still many traces of the Dutch around New York and one can even find tombstones with Dutch texts. The latter is something that unfortunately escapes many Dutch people who visit New York.

Literature

- Duval, Francis Y. and Ivan B. Rigby, Early American Gravestone Art in Photographs, New York 1978

- Eekhof, A.; The Reformed Church in North America (1624-1664), first and second part, 1913

- Inskeep, Carolee, The Graveyard Shift. A Family Historian's Guide To New York City Cemeteries, 2000

- Shorto, Russell; New Amsterdam. De oorsprong van New York, Dutch edition2009

Sources

- The records of New Amsterdam from 1653 to 1674 Anno Domini; Minutes of the Court of Burgomasters and Schepens, Volume I to VI, edited by Berthold Fernow, 1923.

Notes

[1] Eekhof, A.; The Reformed Church in North America (1624-1664), first part, 1913 and Shorto, Russell; New Amsterdam. The origins of New York, 2009.

[2] See: https://friendsofalbanyhistory.wordpress.com/2018/01/16/the-old-burying-places/

[3] Inskeep, Carolee, The Graveyard Shift. A Family Historian's Guide To New York City Cemeteries, 2000

[4] The records or New Amsterdam from 1653 to 1674 anno domini, Volume I, edited by Berthold Fernow

[5] The records of New Amsterdam from 1653 to 1674 anno domini, Volume I, edited by Berthold Fernow

[6] Among others: Inskeep, Carolee, The Graveyard Shift. A Family Historian's Guide To New York City Cemeteries, 2000

[7] http://www.dodenakkers.nl/artikelen-overzicht/foreign-section/north-america/fieldstone-burial-markers-in-the-upper-mid-atlantic-colonies.html and https://www.ncptt.nps.gov/blog/preservation-issues-of-wooden-grave-markers-and-other-wooden-artifacts/

[8] Among other things: https://gaz.wiki/wiki/nl/Reformed_Church_in_America and https://www.rca.org/about/history/. Archival documents up to, say, 1809 can be found in the city archives of Amsterdam.

- Last updated on .