Istanbul - Protestant cemetery of Feriköy

Trade brought the Dutch to many countries in the world, Turkey was no exception. Traditionally, trade with the Ottoman Empire was mainly through the Byzantines who considered themselves invincible in their capital Constantinople. At the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Dutch themselves established diplomatic relations with the Ottoman Empire.

By 1453, the armies of the Ottoman Empire, led by Sultan Mehmet II, had succeeded in conquering the Byzantine capital. For a moment it seemed definitively over with the lucrative trade that supplied Europe with all kinds of exotic goods from the east. The Genoese and Venetians had had their trading houses in the city for a long time and even helped defend it. The conflicting interests led to a war between the Ottomans and Venice, which would last from 1463 to 1479. Florence and Ragusa (Dubrovnik) benefited by taking over the trade of Venice. In turn, Ragusa and Florence and also Venice, were displaced from the Levantine markets by France, England and the young Dutch Republic. In 1569, trade privileges were granted to France, which later served as a model for those to England, the Republic and other European states. The Republic received this privilege in 1612: in that year Cornelis Haga was appointed as the first ambassador to the Ottoman court. The then Republic of the Netherlands already had relations with the Ottoman Empire, but 1612 is the official start of diplomatic relations. In large cities, such as Smyrna (Izmir) and Constantinople (Istanbul), representations were established. That also led to a funerary legacy in Turkey, in Izmir in the form of the remains of the Protestant cemetery and in Istanbul in the form of the "Feriköy Protestan Mezarliği".

History

The current cemetery in Feriköy is actually the second cemetery for Protestants in Istanbul. Deceased from the circles of religious foreigners in the city were buried from the sixteenth century north of Taksim on the so-called "Grand Champs des Morts". This name applied to extensive cemeteries for Armenians, Muslims and other population groups. Immediately after the large military barracks that stood here, the section was for "Franks", or rather Europeans. Behind it was the cemetery for the Armenians and to the east were large fields for Muslims. After Taksim, Istanbul stopped at the time. The green open space became known as early as the eighteenth century as a place where it was good to be. Later, landscape designers from the west came here to see how a big city like Istanbul dealt with its dead on the outskirts of the city. Istanbul's growth, however, was unstoppable. Between 1840 and 1910, the space between Istanbul and rural Şişli, three kilometres away, was transformed from an open landscape into a densely populated urban settlement. Older maps of Istanbul still show this area as one big field of death. However, these cemeteries were not considered as the city expanded. The urban development of the Ottoman capital, influenced by Western ideas, led to the closure of the once-known necropolis that had inspired the reformation of cemeteries in Europe. So that is how it can go.

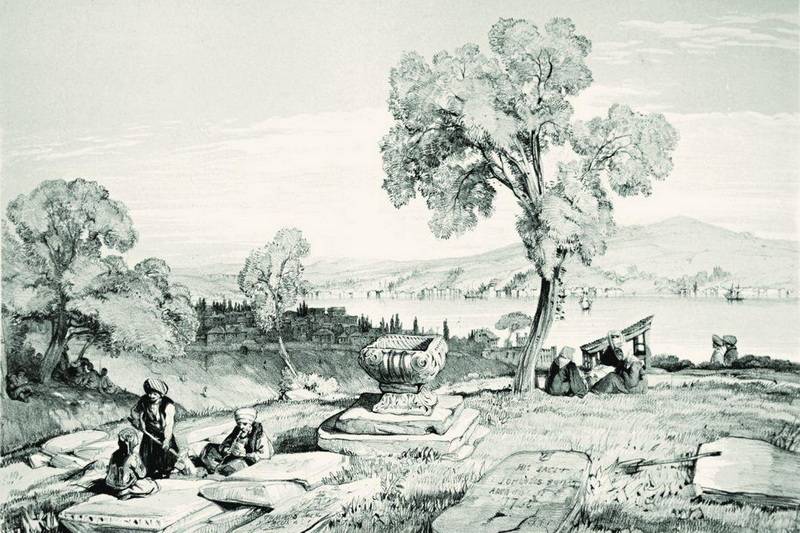

Nineteenth century drawing of the Grand Champs des Morts.

Nineteenth century drawing of the Grand Champs des Morts.

According to nineteenth-century sources, the Christian cemetery was already restricted around 1840. In 1841, Reverend William Goodell, a missionary on the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions to the Armenians, lost his nine-year-old son. The young Constantine Washington died of typhoid fever and was buried in the Western section of the large cemetery. The pastor says that because of violations in the cemetery on February 18, 1842, he had to rebury his son elsewhere. About fifteen meters away, the new grave was dug. But this grave would not have a long life either. The inhabitants of the city were in great need of space for new houses, streets and other buildings. Around 1860 the first construction work began around the old cemetery and in 1863 the remains of a number of Americans, including the one from Constantine Washington Goodell, were transferred to a new Protestant cemetery in Feriköy.

Part of the old cemetery was transformed into a public park, entirely according to Western standards. “Taksim Bahçeler,” or Taksim Park, was officially opened in 1869. Parts of other cemeteries would remain in the area for a long time. Just like the other fields of the dead, they would slowly disappear and make way for buildings.

The new Protestant cemetery

The closure of the old cemeteries and the compulsory construction of new cemeteries for the various ethnicities was carried out by order of Sultan Abdülmecid I. In 1857, for example, the necessary land for the new Protestant cemetery was donated by the Ottoman government to the leading Protestant countries at the time: the United Kingdom, Prussia, the United States, the Netherlands, Sweden, Norway, Denmark and the then remaining Hanseatic cities of Lübeck, Hamburg and Bremen. The Protestant cemetery was officially called "Evangelicorum Commune Coemeterium". The new field of death was about three kilometers from the former cemetery and was laid out west of the main road to the villages that were north of Istanbul.

The first deceased was buried in the new cemetery in November 1858, but the official opening would not take place until the spring of 1859. Although the cemetery was specially laid out for foreign nationalities, the southwestern part of the cemetery was reserved for Armenian Protestants. This part is separated from the rest by a wall. On this small part, Greek, Arab, Assyrian and Turkish Protestants also found their final resting place. These were mainly Muslims converted to Protestantism. Their origin can be recognized by the inscriptions on the funerary monuments that are written in various languages.

Present

The cemetery is still in use today and the graves are issued by the consulates of the countries involved in the cemetery. Since its opening, about 5,000 people have been buried there. Because many older grave monuments from the cleaned-up cemeteries and from Izmir, for example, have been transferred here, the cemetery looks like a funerary museum. There are funerary monuments here that date back to the seventeenth century. Old slabs have been placed against the walls.

The cemetery is divided into compartments. Each country has its own 'courtyard', indicated by signs. Sometimes the interpretation is a bit vague, but based on the texts on the tombstones, each part can be found. Compared to the busy street on which the cemetery is located, it is really a unique resting place behind the wall. It is relatively quiet and only the tall buildings in the area occasionally penetrate the tall trees. Behind the entrance, which is closed with a metal fence, a path leads into the cemetery. To the left is the manager's house, low in relation to the high-rise flats built right next to the cemetery. The path leads directly towards the Armenian part with a small building on the right that looks new. Here one can say goodbye to the dead. Against the wall on the left you can already see large slabs that apparently come from another cemetery. If you follow the path to the middle of the cemetery, you will automatically come face to face with an old chapel, built in a neo-Gothic style from rough blocks of natural stone. Left and right, the funerary monuments stretch out, in all kinds of styles and with inscriptions in all kinds of languages.

The management of the cemetery rotates every two years between the Consulate Generals of Germany, Great Britain, the United States, the Netherlands, Sweden, Hungary, and Switzerland.

Address: Cumhuriyet Mh., Ergenekon Caddesi 58, Istanbul.

Opening hours: daily, except Monday, from 08:00 to 17:00.

Accessibility: The cemetery is easiest to reach by metro that goes to Osmanbey. When you reach the Osmanbey stop and go up via the stairs, on the right you will see a walled area in front of you. This is the French Catholic cemetery. If you walk around this wall to the back of the Catholic cemetery, you will see another walled area with a gate with a cross on it. This is the entrance to the Protestant cemetery.

More information on the Dutch monuments,

Literature

- Obreen, H.G.A.; Grafschriften van Nederlanders te Constantinopel, in: De Nederlandsche Leeuw, volume 22, 1904

Internet

- Brian Johnson; Istanbul's Vanished City of the Dead: The Grand Champs des Morts, 2005; https://fountainmagazine.com/2005/issue-49-january-march-2005/istanbuls-vanished-city-of-the-dead-the-grand-champs-des-morts

- Feriköy Protestant Cemetery https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferik%C3%B6y_Protestant_Cemetery

- Protestant cemetery Feriköy on the website Heritage in Turkey

Reference: SC-TUR-003

- Last updated on .