Rome - Monument of Dutch Zouaves

In the nineteenth century, numerous new states emerged as kingdoms fell. This is particularly true for the Italian peninsula. In the first half of the nineteenth century, this consisted of a conglomeration of smaller areas of power within the center the 'Ecclesiastical State', the pope's area of power in Rome. When this area was threatened, the pope called on volunteers to fight for its defense.

What a few thousand Dutch people had to do with this is related to the Catholic emancipation in the Netherlands in the second half of the nineteenth century. These papal warriors left few traces in the Netherlands, but in various cemeteries in the Netherlands the text "Papal Zouave" sometimes stands out. A search for the still existing funerary monuments leads to a (far from complete) first overview.

What was the battle about?

Since the eighth century there was an Ecclesiastical State (also called Papal State), a piece of land donated by King Pepin the Short halfway between the boot of Italy. Pepin had been crowned King of the Franks by the Pope himself in 751. In the centuries that followed, the Ecclesiastical State was repeatedly targeted by its warlike neighbors but was able to retain authority for a long time. After initial expansion of the territory, the power of the Ecclesiastical State declined again after the sixteenth century. With the invasion of the French in 1797, large parts of the Ecclesiastical State were taken by them. A year later, the Pope was even deposed, and the Ecclesiastical State effectively ceased to exist. After initially being restored in 1800, it was overrun by the French in 1808 and only restored after their departure in 1815. When a national movement opposing foreign domination arose in Italy in the nineteenth century, the Ecclesiastical State also proved to be an obstacle. In 1859, the territory of the Ecclesiastical State was greatly reduced, but with the help of foreign troops it managed to survive. After it turned out that the pope did not want to join the national struggle led by the revolutionary Garibaldi together with the Kingdom of Turin, the Ecclesiastical State was declared an enemy.

Defense of the Ecclesiastical State

As early as 1849, the French provided a small force to defend the Ecclesiastical State. However, they could not prevent large parts from being lost. In 1860, Pope Pius IX called on the entire Catholic world to send young, unmarried men. These volunteers were given the name Papal Zouaves in imitation of the French zouaves. The original zouaves were part of a light infantry unit in the French army, formed by members of the Algerian Berber tribe Zouaouwa, who fought against rebellious Berber tribes in colonial Algeria from 1830.

Of the volunteers who then came to the pope's aid, remarkably enough, a third of the total came from the Netherlands. These numbers were undoubtedly related to the fact that not long before the Catholic Church in the Netherlands had been restored.

Situation in the Netherlands

Despite the freedom of religion, the French brought with them in 1795, there was no such thing for Catholics in the Netherlands until 1853. The organization of the church was led from Rome and a hierarchy hardly existed in the Netherlands. That changed after 1853 when the dioceses in the Netherlands were restored. After almost three hundred years, Dutch Catholics were given bishops again, were allowed to found churches and monasteries and openly profess their faith. This triggered an enormous emancipation, with the most striking result being the construction of hundreds of churches and numerous cemeteries of their own. However, there was great poverty among many Catholic families, but at the same time the Catholic revival brought with it a new view of the world that many young people wanted to explore. The pope's appeal in 1861 was well received. That some of them would pay for it with their lives would not have occurred to them immediately. Despite this, most of them returned in one piece and some of them mention had their service for the pope mentioned on their tombstones.

The combat in Italy

In the Netherlands, a number of fathers and pastors were particularly active in recruiting young Dutch men for the fight in Italy. The Amsterdam father Cornelis de Kruyf (1813-1874) was one of them. He regularly preached about the duty of the boys and found acclaim in the Catholic press. The journey of the zouaves-to-be went via Brussels to Marseille and from 1864 via Oudenbosch in Brabant. There, Father Hellemons (1810-1884) prepared the boys for their journey. Then they went by train to Marseille and then by boat to a safe harbor near Rome. The cost of the trip was covered through organized donations.

From 1861 the pope's small army fought against Garibaldists and from 1867 the French came to the pope's aid again. A number of major battles followed in those years, such as the Battle of Mentana in 1867.

Those who were approved for the papal army as healthy youngsters often did not await adventure in Italy, but rather boredom, diseases, and other harsh conditions. After a short training there was waiting and marching. The fighting, particularly at Mentana and Monte Libretti in 1867, eventually costed several dozen boys their lives.

Fallen in Italy

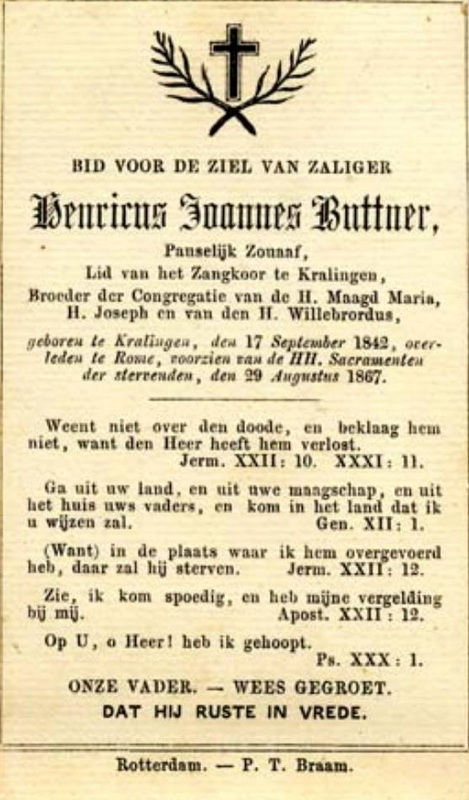

The Dutch who died during the battle against the Garibaldists were given a final resting place in Italy. Not all the names of those killed are known or if the name is known, we sometimes do not know their final resting place. This applies, for example, to Henricus Joannes Büttner (born 1842). This young Catholic from Kralingen went to Rome in 1866 to join the pope's army. He died in Rome in 1867 because of cholera. Apart from a prayer card commemorating his death, little else is known about him.

Prayer card for zouave Büttner who died of cholera in 1867

Prayer card for zouave Büttner who died of cholera in 1867

(collection Wim Knoops)

In the Campo Verano cemetery in Rome there is a genuine Zouave monument, erected at the end of 1867 after the battle of Mentana on 3 November of that year. The monument mentions at least 18 Dutch people who are buried there or are only commemorated:

- Eduard van Bambost, Overslag (born 1840), died on 3 November 1867 in Mentana. His death was entered in the death register of the municipality of Overslag in June 1869.

- Antonius (Antoon) Marinus Bongenaar, Etten-Leur (born 1846), killed on 13 October at Monte Libretti in the run-up to the battle of Mentana.

- Franciscus van den Boom, Nistelrode (born 1838), killed on 13 October near Monte Libretti. At the end of October 1867, several Dutch newspapers reported that Van den Boom had been taken to hospital wounded.

- Joannes Stephanus Crone, Groningen (born 1830), killed at Monte Libretti.

- Henricus Joannes van den Dungen, Oisterwijk (born 1838), killed in Mentana.

- Gerardus Johannes Thomas Erftemeijer, Amsterdam (born 1839), killed on 3 November in Mentana by a bullet in the chest. A friend of his who was with him when he died later returned Erftemeijer's watch to his parents in Amsterdam.

- Everardus (Evert) Heijmans, Dussen (born 1843), killed in Mentana.

- Petrus Nicolaas Heykamp, Amsterdam (born 1843), killed on 5 October 1867 by a bullet in the chest near Bagnorea while protecting his captain. He is commemorated on the monument. His tomb is in the Cathedral of Bagnorea.

- Henricus van Hooren, 's-Hertogenbosch (born 1838), killed in Mentana.

- Pieter Jong, Lutjebroek (born 1842), killed as a hero in October at Monte Libretti. Around his dead body were found fourteen enemies killed by him. Jong is commemorated in Lutjebroek with a statue that was unveiled in 1917 and there is also a street named after him.

- Jacobus Melckert, Zierikzee (born 1827), killed on 3 November in Mentana.

- Antonius Otten, Veghel (born 1842), wounded at Monte Libretti and transferred to the hospital in Rome. There he was visited by the Pope and received a medal. Not much later he died.

- Cornelis Pronck, Avenhorn (born 1843), killed in November near Mentana.

- Godefridus J. van Ravensteyn, 's-Hertogenbosch (born 1842), was seriously injured in his leg at Monte Libretti and transferred to the hospital in Rome where he died in early November.

- Enricus Roemers, Bloemendaal (born 1842), wounded in Mentana and later died.

- Henricus A. Scholten, Haarlem (born 1844), wounded in October near Monte Libretti, later died in November.

- Jacobus Schrama, Warmond (born 1844), killed on 3 November in Mentana.

- Joannes Zandvliet, Delft (born 1846), killed on 3 November in Mentana.

The monument to the fallen zouaves at Campo Verano cemetery in 2023.

The monument to the fallen zouaves at Campo Verano cemetery in 2023.

In May 1868, a mass grave was unearthed near the battlefield of Monte Libretti in which both zouaves and Garibaldists lay. Among the dead, the bodies of Franciscus van den Boom, Johannes Crone, Godefridus van Ravestein, Pieter Jong and Antoon Bongenaar were found. The remains were then interred in a crypt to the left of the altar of Our Lady del Passo near Montelibretti.

In the newspapers of that time, some other Dutch dead are also mentioned that are strangely not mentioned on the monument, such as Willem van Hulst (1836) from Groningen, H. Bakker from Ter Aar, Simon T. Franken from Dronrijp, Melcher from Culemborg. For some, there is a simple explanation, as for Van Hulst. He was reported dead but found in an enemy hospital in late November 1867. There, his left leg was deposited above the knee. Van Hulst returned to Veghel where he died in 1895, unmarried.

A number of the fallen, not mentioned on the monument, sometimes died a few months later from their wounds. Jacobus van Hees (born 1844) was seriously injured near Mentana and died on 21 December 1867. His body was transferred to the Netherlands where it was buried in Delft at the end of January 1868. Cornelis J. Vogelaar (born 1838), sergeant with the zouaves, also died much later. He died in Rome on 20 January 1868. Whether his body was transferred is not known. A fund was soon formed for the returning zouaves that had survived but had been maimed.

A total of 144 people were killed among the zouaves, a most of them are mentioned on the monument erected for them at Campo Verano. The volunteers under Garibaldi suffered many more casualties and several hundred of his troops were also taken prisoner. The zouaves who had fought in the battle later received a so-called Mentana medal.

The monument

The monument on which the Dutch are commemorated and where most of them are also buried, was erected in the course of 1868. The foundation stone was laid on June 3, 1868. Initially, Pope Pius IX wanted to erect the monument commemorating the battle of Mentana in the church of Monte-Rotondo, but the church proved unsuitable. After that, a location was found on Campo Verano near the Basilica of Saint Lawrence outside the Walls. The monument has an octagonal base placed within a circular floor plan. The circle around is fenced off with a fence of poles with iron fences between them. In the center of the fences is a metal cross with the papal seal and the name of Pope Pius IX and the year 1867. The octagonal base stands on several steps and contains text plates of marble with metal letters on all sides. For each battle, prior to the final at Mentana (here called Ad Nomentum in Latin), are the names of the victims, all in Latin. The names are not always written correctly, but the word Hollandus is very recognizable. One of the text plates contains the following text (loosely translated from Latin):

To the bravest Indigenous and foreign soldiers who in the year 1867 shed their lives with their blood, fighting in various battles for religion and the inviolability of the city, against the forces of the father murderers.

Pope Pius IX ordered the creation of this grand monument, in which the sacred memory of the most deserving children of his will and their virtue are passed on to posterity.

Above the octagonal base, the monument rejuvenates into a drum with some texts and on either side images of young women, one a veiled woman with a chalice and Bible in her hand and the other with plants and dressed in a bear skin. The most important part is located on top of this drum and a large statue of a kneeling knight (a zouave) receiving a sword from the hands of Saint Peter, placed against a spear with flag.

The memorial was modified after the fall of the Ecclesiastical State by replacing one of the text plates with an offensive text. This was eventually removed, and the texts may have been adjusted afterwards, which may explain why some names are missing. In 2023, the monument is in questionable condition, but it is still clearly visible because it is freely placed on a kind of square in the cemetery.

Buried elsewhere.

Elsewhere in Italy, for example in Albano, three Dutch people who died of cholera are commemorated: Jacobus van der Meyden (Drunen), Gerardus Theodorus Peters (Beek) and G.J. van Ophem (Haarlem). In the cathedral of Bagnorea is the already mentioned tomb of Petrus Nicolaas Heijkamp who was killed in the battle of Bagnorea in 1867. Dutch people are also buried in some other cemeteries in the vicinity of Rome.

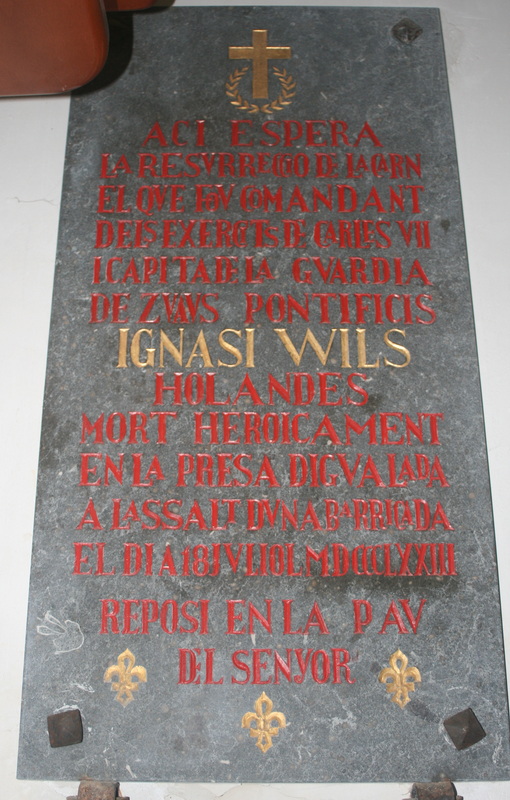

The memorial plaque for zouave Wils in the church of Igualda in Spain

The memorial plaque for zouave Wils in the church of Igualda in Spain

(courtesy of the Zouave Museum of Oudenbosch).

Not all zouaves who died in battle fell in Italy. There were those who wanted to continue fighting after the papal zouaves were disbanded. For example, some of them went into battle as Carlist zouaves in Spain. Some Dutchmen, such as Johannes Hof (1834) and Ignatius Wils (1849) fell there at the battle of Manresa. Wils had even fought on the French side in the Franco-Prussian War and was an experienced soldier. In 1872 he arrived in Spain as colonel-commander of a battalion of Carlist zouaves. In the storming of Igualada, he and Hof were killed. In the church of Santa Maria de Pinos, a commemorative plaque has been incorporated into the floor in memory of Wils who died a hero's death.

Not killed, but reviled

About five percent of the zouaves deployed were killed. It was not the struggle that was the biggest cause, but infectious diseases or other inconveniences. For example, zouave Feije Bies (1843) broke a toe during an exercise and had previously been bitten by a snake. Unable to take part in the battle, he returned to the Netherlands in August 1869. In Amsterdam he was nursed in the “Binnen-gasthuis”, but amputation of his toe did not help. He died on 13 February 1870 and was buried at the Liefde cemetery in Amsterdam. At the funeral there was no representation of the Invalids-Zouaven Fund, and they did not take care of the funeral, so Bies was buried of the poor as it was called. In Catholic circles, shame was spoken of the fact that Bies had not received any military honours. And so, this zouave has disappeared into oblivion, for his grave was presumably soon cleared.

The exact number of deaths among the Dutch part of the zouaves is not known. Many of the pope's fighters returned to the Netherlands after a while. For many, that was a big disappointment. Their stories were not always believed, simply because their listeners had no idea what Italy looked like. In addition, most of them had lost their Dutch citizenship because they had entered foreign military service without permission. The former zouaves were looked down upon outside their own circle, but among Catholics they were heroes. After all, they had fought for the pope and received his blessing.

What losing Dutch citizenship meant is evident from the story of Folkert L. Rijnja (1849). Rijnja returned from Rome in 1869 to fulfill his military service here, but that did not take place because it turned out that he had lost Dutch citizenship. Somehow, he still served, but later it caused him trouble again. Rijnja had set up a successful carpentry and contracting business in the village of Woudsend and was a well-known figure in the village. When he ran for city council in 1925, his name was not added to the electoral list. This on the grounds that he had been in foreign military service. A request to add him was rejected.[i] [1] His old-age pension was also first withdrawn and then re-granted. When Rijnja died in 1937, however, this was widely reported in the newspapers. Rijnja is said to be the last Frisian zouave to die. The story of his findings was once again widely reported. Rijnja was buried in Sint Nicolaasga, where the tombstone was placed next to the monument to the Frisian zouaves in 2020.

Thanks to:

- Mr. Wim Knoops, archivist church archive of the St. Lambertus church in Kralingen

- Mrs. Marijke Zonneveld-Kouters of the Zouave Museum

- Mr. Maikel Galama, family researcher

Note

[i] Bontekoe, G.A.: Pauselijke Zouaven uit Drenthe geboortig, 1969.

Literature

- Bontekoe, G.A.; ‘Pauselijke Zouaven uit Drenthe geboortig’ in: Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak, 87ste jaargang, Assen 1969.

- Nota, H.; Een vergeten leger. Geschiedenis van de Friese Zouaven, Bolsward 2020

Internet

- Beeldbank historische vereniging Oud Stede Broec [consulted 31 May 2023]

- Westfries Genootschap: Pieter Jong, de held van Lutjebroek [consulted 31 May 2023]

- Stichting Nederlands Zouavenmuseum in Oudenbosch [consulted 31 May 2023]

- Last updated on .