Dejima - Nagasaki in the 17th century

When the Dutch were forced to move to the island of Dejima in 1641, they ended up in the town of Nagasaki. This town had only increased in importance in the previous century thanks to the Portuguese who had made their first contact with the Japanese on a nearby island in 1543. The Portuguese rapidly started trading with Japan – and evangelising the Japanese. In 1569, converted daimyos (feudal lords or landowners) gave the Portuguese permission to use the port of Nagasaki as their base. The natural harbour of Nagasaki was eminently suitable for this purpose as it was sheltered from the sea and strong winds but trade from Nagasaki only really began in earnest in 1571. Up until then it had been a sleepy fishing village of little significance.

Christianity

The port grew enormously in the last quarter of the 16th century as trade increased but times were turbulent. Nagasaki was so important to the Portuguese that, in 1580, they placed the town under the control of the Jesuits. This was possible because the local Catholic landowner transferred jurisdiction to the Portuguese. Whereas elsewhere in the vicinity, Christians faced increasing persecution, Nagasaki appeared a safe haven for them. In 1587, Nagasaki once more came under the control of the Japanese when Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a powerful Japanese warlord, seized the town, his intention being to unite Japan. The Christians in Nagasaki were subsequently left in relative peace, probably because of the importance of the trade. Meanwhile, the Portuguese continued their mission to convert the Japanese to the Catholic faith, as did the Spaniards. However, in 1596, the Japanese got the idea that the Spanish Franciscan order had plans to carry out an invasion and, on 5 February, Hideyoshi had 26 Catholics crucified on these grounds. The Portuguese traders were, as yet, left alone but, in the continuing fight to unite Japan, a ruler emerged who did not hold with Christianity at all: Tokugawa Ieyasu. When, around 1614, it became apparent that the English and the Dutch were also prepared to trade with Japan without any religious emphasis, Tokugawa forbade Catholicism in Japan. Missionaries were banned and local landowners were forced to renunciate their Christian faith. Those that did not wish to do so often left Japan for the mainland of China or other towns in the region where they could conceal themselves among the rest of the residents. The years after 1614 were violent years during which thousands of converted Japanese were killed. In 1637, the Dutch showed that they did not have a great liking for the Catholics by participating in the crushing of the Shimabara rebellion. This was the last Christian uprising in Japan. The rebellion was definitively quashed in 1638, partly by means of the cannons made available by the Dutch, but this did not avail them of more rights or privileges.

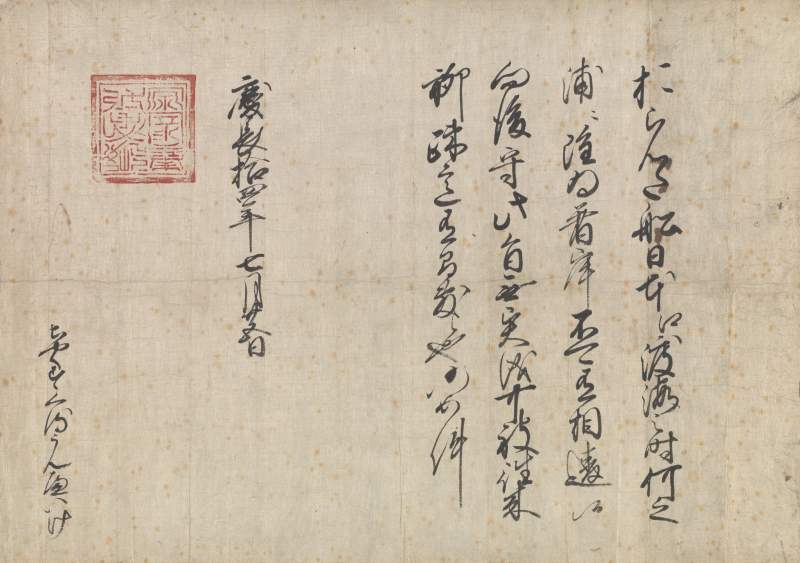

Dutch Japanese trading pass 1609 (NL-HaNA, Nederlandse Factorij Japan, 1.04.21, inv.nr. 1A1)

Dutch Japanese trading pass 1609 (NL-HaNA, Nederlandse Factorij Japan, 1.04.21, inv.nr. 1A1)

Because of the fear of new converts, from 1616, the Portuguese were only allowed to trade from Nagasaki, whereas the Dutch had set up a trading post in Hirado. Tokugawa Iemitsu, Tokogawa Ieyasa's grandson, strove to isolate Japan altogether. In 1634, he decided to construct an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki to which the Portuguese would be confined. Until that time, the Portuguese had been able to settle anywhere in Nagasaki. The island, financed by 25 wealthy Japanese merchants, was ready in 1636. Dejima or Tsukishima (island that sticks out), as it was called, was less than one and a half hectares in size.

From Hirado to Dejima

The Portuguese were not able to use the island for very long because, in 1639, they were deported and the Shogun imposed a ban on trade with the Portuguese, on pain of death. The fact that the situation was serious became apparent when, in the summer of 1640, a Portuguese delegation came to Japan to plead their case. Sixty members of the delegation were executed without mercy and only thirteen of the crew were able to return to Macao to proclaim the bad news. Initially, the Dutch thought that no restrictions would be imposed on them but, in November 1640, the Inspector General Inoue Chikugo-no-kami Masashige arrived to inspect the Dutch trading post in Hirado. After combing all the storehouses and houses for Christian objects, he ordered chief factor François Caron to demolish the VOC´s newly built warehouse. The Shogun was apparently irritated by the fact that the Dutch had erected a building like that with a gable stone carrying the inscription 'Anno Christi 1640'. The stone tablet or plaque indicating the date of the construction of the building was deemed a 'Christian utterance' and therefore an insult to the Shogun. On 10 February 1641, Maximiliaan le Maire, who had succeeded Caron as chief factor, received orders to leave Hirado and move to Dejima[1]. This took place on 24 July 1641. In his description of 'Onzen handel in Japan (Our trade in Japan)', Valenyn describes the island as follows: ‘Dit Decima is een zeer klein island, ‘t geen na de Stads-zyde 382, dog na de Zee-kant 714 voeten lang (loopende hoogswyze zoo veel uit, als 't na de Stad toe inbuigd) en 216 voeten breed is (Dejima is a very small island measuring 382 feet in length on the town side, yet 714 feet on the sea side (fanning out towards the sea) and 216 feet in width. In de breedte van 't zelve, na de kant van the Baay, zyn 2 groote Poorten, waar door alle waaren vervoerd werden, en in ‘t midden aan the Land-kant, in des zelfs lengte, is 'er een, waar uit men, over een steene brug, in de Stad gaat, daar ook altyd des Stadvoogds wacht, een Schryver, and een betaster is (In the width, on the side facing the bay, there are two large town gates through which all goods are carried and in the centre of the land side there is one gate giving access to the town over a stone bridge, always guarded by the official town guard, a clerk and an inspector.’[2]

A new beginning

The description of the island continues to talk about the buildings that comprised two rows of houses and warehouses. The Dutch had to pay a rent equalling 19,530 guilders for the use of the island. This rent went to 25 local families who had enabled the construction of the island. Besides the houses, the VOC had two warehouses, the Lelie (Lily) and the Doorn (Thorn), a large kitchen, a pantry and several small houses for the interpreters and the Governor's agents on the island. There was also a garden on the island. Later a hospital was added, something that proved an absolute necessity in the period that ships lay in the harbour. Not only did the new location entail less freedom of movement for the Dutch but a rule stipulating that a chief factor may not serve for longer than a year in Japan was also imposed. This was supposed to prevent people from learning too much from the Japanese, such as their language, and to prevent chief factors from taking things into their own hands and trading under their own initiative. They were, however, permitted to return after a year to pick up their work as chief factor again. This restriction was quashed many years later, thus allowing chief factors to remain in Dejima for consecutive years. Some were obliged to stay anyway, for example, if their successors did not turn up.

Nagasaki was also important for the trade with China and the Chinese sailed their junks in and out of the port the whole year round. However, it was particularly busy between August and early December. In this period, the Dutch commercial vessels lay in the harbour and the population on the island of Dejima increased considerably, increasing the pressure on the hospital as a result. When the ships sailed from Dejima, there was not only a new chief factor but sometimes also new employees. The number of employees that normally lived on Dejima was quite limited. After the departure of the ships, a long period of waiting began for them, the monotony of which was only relieved by trade with the Chinese, frequent contacts with the Japanese and the annual official visit to the Shogun's court in Tokyo.

The interpreters on Dejima had an important role as they formed the link between the Dutch and the Japanese. The fact that this was extremely difficult was beautifully formulated by chief factor Hendrik Doeff who, out of necessity, stayed on Dejima from 1799 to 1817. He describes how the interpreters only learned Dutch through contacts with the Dutch in Japan. When new officials arrived, they had the greatest difficulty in understanding the interpreters because of their pronunciation and ‘hunne geheele taal, naar de Japansche spraakwendingen gewijzigd, door die aankomelingen ten hoogste moeijelijk zijn ('their whole language, adapted to match the Japanese turn of phrase, is very difficult for newcomers to understand').’[3]

[1] Valentijn, p. 36.

[2] Valentijn, ibidem.

[3] Doeff, p. 2.

- Last updated on .