Izmir - Protestant churchyard

In Izmir, formerly Smyrna, there are still several Christian cemeteries and a Jewish cemetery to this day. Until the beginning of the twentieth century there were a number of neighborhoods in the city for Greeks, Armenians, 'Franks' [1], Jews and Turks, all of whom had their own cemeteries. The oldest cemeteries were closed down early in the eighteenth century due to urban expansion. On the west side of the city there were large Jewish and Muslim cemeteries and on the east side were three European cemeteries. These could be found until the thirties of the twentieth century at one of the bridges over the river Meles, which gave access to Smyrna on the east side. This so-called caravan bridge has now disappeared and nowhere in the area is there anything to be found of a cemetery. There is still a Jewish cemetery in the area. The current Christian cemeteries are to be found further from ancient Smyrna, including in Buca, Bornova and in Karabağlar, on the road to Gazimir. There are burials to this day. Here are also some graves of the Dutch family Dutilh, a trading family that has continued to live in Izmir.

Caravan Bridge Izmir

Caravan Bridge Izmir

Dutchmen in Smyrna

The city of Smyrna, founded by the ancient Greeks in the eleventh century BC, was part of the Ottoman Empire from 1415. Its convenient location on a large bay, easily accessible via the Aegean Sea, ensured that the city grew into an international trading city. That was also because Smyrna was a hub in trade via the Silk Road. Western merchants quickly found the city. Probably the Dutch merchants came to Smyrna as early as the sixteenth century, then still trading under the French flag. After 1612 they were allowed to trade under their own flag. In the same year Cornelis Haga (1578-1654) was appointed as the first ambassador to the Ottoman court for the Republic of the Netherlands. The republic had previously had relations with the Ottoman Empire, but 1612 is the official start of diplomatic relations.

The first consul in Smyrna was appointed in 1656 and a small Dutch community arose. Many of the Dutch are now unknown in name, but one of them we know a little more. His name was Daniel Jean de Hochepied (1657-1723). He came from a French Huguenot family and his father traded in silk fabrics in Amsterdam. De Hochepied first set foot in Smyrna in 1678. That was not a deliberate move, but more to linger in other spheres because of an unfortunate love affair. In Istanbul he met the daughter of the Dutch ambassador and married her. Because the home front was not pleased with this marriage, De Hochepied decided to extend his stay in the Ottoman Empire. Through his contacts he became consul of the Dutch community in Smyrna in 1688. At that time there were as many as 10,000 foreigners living in Smyrna, with their own churches, cemeteries, hospitals and other facilities. De Hochepied also acted for friendly powers and looked after their affairs within the Ottoman Empire. As a reward, De Hochepied obtained all kinds of favors and titles for his work, for instance in 1704 he received the title of baron from Hungary. Some of his children would also reach high positions, including ambassador in Istanbul.

Another family which succeeded business in the Ottoman Empire were the Van Lenneps. In 1731 David George van Lennep came to seek his luck in Smyrna. Soon he found fortune in business, while not finding love. Eventually, Van Lennep married a young woman from the Leidstar family, who had a large trading house in the Ottoman Empire. The De Hochepied and Van Lennep families built their lives on the Aegean coast and thanks to their child-rich families, they soon became among the most prominent families in Smyrna.

Because numerous marriages were concluded within the European community of Smyrna, the international community was able to leave its mark on the city in the eighteenth century. The European quarter in the city was among the most pleasant places in Smyrna. To escape the hustle and bustle of the city, many wealthy families often had a house built far outside the city.

The Dutch Churchyard

The Dutch had their own church, hospital and cemetery in the old town. These can still be found today in the Alscancak district. The environment here has changed beyond recognition after 1922, partly due to the great devastation caused by the Greco-Turkish War. At least 70 percent of the city burned down. The fact the church survived the Greek-Turkish struggle may be called a miracle. However, many of the Dutch houses, often just like many of the other houses made of wood, were lost.

Bord bij de ingang van het kerkhof.

Bord bij de ingang van het kerkhof.

The first burial in the churchyard probably took place in 1663. The cemetery remained in use until 1874. After that, the Felemenk Bahce (SC-TUR-004) was put into use further outside the city. The cemetery was not used for burials exclusively by the Dutch, as evidenced by the Swiss and English texts on some funerary monuments. Church and cemetery remained in the hands of the Dutch state at the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, on condition that it would be used for religious purposes. For that reason, the Dutch state has rented the church to the Greek Orthodox Church 'Aya Fotini'. The current appearance of the church, in an English style, probably dates from 1908. An English church in Buca, built by English trading families in 1868, was probably the model for the church. As far as is known, no research has ever been done into the church and the cemetery. A publication cannot be found. Nevertheless, there are lists and references to be found from which a number of things can be concluded.

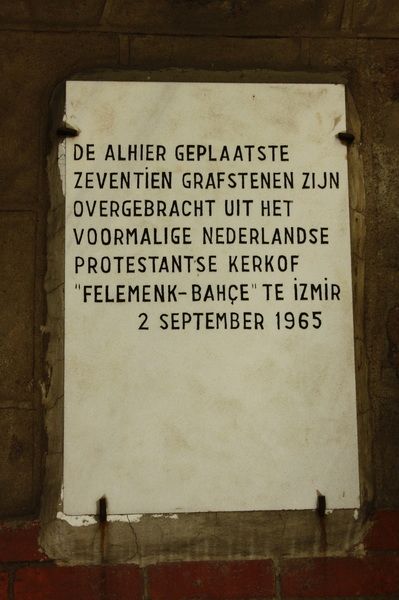

In the cemetery you can find a few dozen richly decorated funerary monuments from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century with names of Dutch families that recall the flourishing period in trade relations. Some of the tombstones are no longer in their original location. In 1965, 17 gravestones were transferred from the old cemetery to here. That was a decision of the then honorary consul Hendrik F.G.M. Dutilh (1929-). A bricked-in stone in the cemetery recalls this event.

Memorial stone in memory of the transfer of the funerary monuments.

Memorial stone in memory of the transfer of the funerary monuments.

In 1950, only 25 Dutch people were known to the consulate. Churchgoers were hardly there anymore. As a result, preserved houses fell into disrepair and many of the traces of the Dutch were lost. Nowadays there are more Dutch people in the area, attracted by the flourishing tourism in the area.

Impression of the churchyard

Today, the church is largely hidden from view by the surrounding vegetation, but after entering the cemetery, the funerary monuments immediately catch the eye. Most of the older funerary monuments are slabs of marble on a sort of tomb. In a number of funerary monuments, this tomb has been richly elaborated with symbolism of death. The texts and effigies on the slabs are often elaborated. In the first instance, the texts are mainly written in the Latin script. In between, words like "Narden" (Naarden) or "Ollandiae" (Holland) point to the origin of the dead buried here. Only a single slab has a text written entirely in Dutch..

Overview with some marble tombstones.

Overview with some marble tombstones.

In the cemetery not only the members of the Dutch trading families were buried, but also the sailors or passengers who died on board their ship en route or in the port. Among the inscriptions we will of course find the names De Hochepied and Van Lennep. Other Protestant families in Izmir, from England, Switzerland or Sweden, also found their final resting place in the cemetery.

The more neoclassical funerary monuments in the cemetery are nineteenth-century and refer to tragic losses of spouses, children or other family members. The execution and style of the funerary monuments of many of the Dutch has a representation that tends to slabs from a church floor. However, we hardly encounter the Latin language used on such slabs in the Netherlands. In fact, we rarely encounter such slabs, certainly from the seventeenth century, in Dutch cemeteries. However, there is a comparison with what can be found at the Dutch cemetery in Livorno in Italy.

Overview with slabs.

Overview with slabs.

There is a small treasure trove of Dutch funerary culture in the middle of modern Izmir. Four hundred years of relations also yields this.

Noot

[1] Name in the Ottoman Empire for Western Europeans

Literature

- Contemporary Turkish culture in the Netherlands and in Turkey/Hedendaagse Turkse cultuur in Nederland en Turkije, verkenning, in opdracht van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken en in samenwerking met het Ministerie van OCenW, 2004.

- Heylen, Sabine, 'Nederlandse diplomaten en ondernemers in de Levant'; in: Genealogie, tijdschrift voor familiegeschiedenis, jaargang 14, nr. 2, juni 2008.

Internet

- List of graves in Alsancak: Levantine Heritage

- Photo's from 1980: Online-begraafplaatsen.nl

Header: De golf van Smirna, Gerard van Keulen (1720)

Reference: SC-TUR-002

- Last updated on .