The unfortunate death of Henry Heusken

How a resident from Amsterdam ended up in Japan via America and found a gruesome death. That is in short the story of Henry Heusken. Heusken was born in Amsterdam, son of Joannes Franciscus Heusken and Joanna Smit, both from a Catholic family. They were married on April 25, 1827. Joannes was a soap maker at the time and according to the records Henricus Coenradus Joannes, as Henry's Christian name was, was their only son. Joannes Heusken died in 1846, when Henry was only fourteen years old. At the time Henry was staying at a boarding school in Breda, no doubt a Catholic. At the age of fifteen he came back to Amsterdam. Over the next six years, Henry tried to follow in his father's footsteps in the family business. He was responsible for the care of his mother who was not in the best of health. According to the population register of Amsterdam, Henry lived at various addresses in Amsterdam around 1853 including Leidsegracht 64, Oudezijds Achterburgwal 10 and Nieuwendijk 7. In one of the registers he is known as an office worker. That must have been after unsuccessfully trying to continue the family business. In 1853, when Henry was 21 years old, he decided to emigrate to America. What remained of the family property must have been enough to support his mother.

New York

Once in America, Henry didn't immediately have luck on his side because he hardly made any money. He was naturalized and adopted the name Henry Conrad Joannes Heusken. Life in New York was tough and Henry lived from small jobs given to him by the Dutch community in the city. In 1855 he was recommended by reverend De Witt and others to Townsend Harris as Dutch interpreter in Japan. Henry spoke English in addition to Dutch and also mastered the French and German languages. Harris was appointed the first Consul General of the United States in Japan, who was looking for a personal assistant and translator. The fact that he was looking for someone who was able to speak Dutch had to do with the fact that the Japanese only used that language for diplomatic matters. The reason for this was that from 1641 until then the Netherlands was the only Western country allowed to trade with Japan. Japan therefore only knew Japanese-Dutch interpreters. All other languages had to be translated through Dutch. This was a big opportunity for Henry. He was offered an annual salary of $1,500, but that would not take effect until he started his work in Japan. To cover his expenses he got $750 in advance.

To Japan

Henry's departure from New York on the 25th of October 1855 would be final, something he probably didn't assume. Henry traveled with the steam frigate USS San Jacinto, a U.S. Navy ship. On that day, Henry also started his diary. In the first words he wrote, his hopes went out to a safe voyage of the San Jacinto. Among other things, he wrote that he had been in New York for three years and that he was going to miss his friends. Henry did not write down his innermost emotions, but rather described what happened.

While Henry was making the journey by sea, Towsend Harris was on his way by land to the port of Penang in Malaysia. There, the San Jacinto arrived in April and then again Henry wrote in his diary. After all kinds of activities in Bangkok where Harris concluded a new trade agreement with the King of Siam, the company left for Japan on 1 June. Along the way visits were made to Hong Kong, Canton and Macao. On his way to Shimoda, a port city where the first consulate was opened, Henry translated a large number of letters from English into Dutch. On Saturday 23 August 1856, Harris and Henry went ashore and visited the locations assigned to them to establish their consulate, the Gyokusen-ji Temple. For the first few weeks, while the ancient temple was being prepared, Henry worked from the ship that took him to Japan. After the temple was ready, the two men would work intensively for several years on the negotiations for the treaty that the United States of America wanted to conclude with Japan. This Treaty of Amity and Commerce, also known as the Harris Treaty, was signed by Japan on 29 July 1858.

Earlier, Harris had reported to Washington about Henry, being a kind and peace-loving man who never acted rudely or violently toward the Japanese and was much loved. In his personal news, however, Harris was a little more direct about Henry. On Wednesday 3 December 1856, he wrote "I believe that Mr Heusken only remembers when to eat, drink and sleep – any other affairs rest lightly on his memory", which meant that the physical needs were most important to Henry. In other cases, Harris tried to warn him not to be late. On 23 December Harris recounted in his news about Henry that he had taken an unarmed walk had been threatened by a Japanese man with a sword. Harris then advised Henry never to walk the streets unarmed again.

After the treaty with Japan was signed, in July 1858, the American consulate was moved to Edo (as Tokyo was then called). The consulate was also located here in a temple complex, that of Zenpuku-ji in the Minato district that had existed since the ninth century. Henry quickly became one of the most public foreigners among the Western powers who then stayed in Edo.

Life in Tokyo

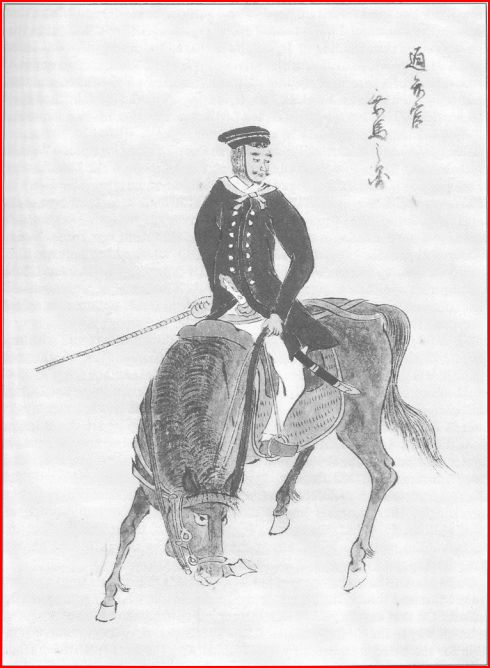

Already in Shimoda Henry had regularly ridden a horse. He continued to do so in Tokyo, where he often made trips. Horse riding in Japan had always been a privilege for the samurai. Samurai literally means 'he who serves'. They formed the warrior class in pre-industrial Japan and from the twelfth to the late nineteenth century samurai formed the armed forces of Japan. The samurai represented ancient Japan under the Tokugawa Shogunate which united Japan in the seventeenth century. The samurai struggled with the upheavals that Japan experienced from 1853 onwards.

Portrait of Heusken

Portrait of Heusken

Pro-imperialist nationalists were opposed to the proponents of the shogunate. In addition, there were also other anti-Western forces in Japan. In March 1860, for example, the Japanese Prime Minister was assassinated for his pro-Western stance. Several Westerners, including two Dutch captains, were also killed simply because they were foreigners. In this climate, Henry still felt comfortable to walk the streets and perhaps also relied on his knowledge of the Japanese language. Unfortunately Henry stopped writing in his diary after June 1858, so we don’t know what drove him. It wasn't until 1 January 1861, Henry started writing again, and now about the dangers of samurai groups planning to attack consulates. On 8 January 1861, Henry wrote his last sentences in his diary. In his diary we read nothing about his contacts with Japanese women (he even turned out to be married and have a child) and how familiar he felt in his environment. That this attitude would be fatal to him was something that came as a shock to the foreign community.

The evening of 15 January 1861

Henry's experience and knowledge of Japan was also popular with other powers. His involvement in previous negotiations made him a much sought-after interpreter. On the evening of 15 January 1861, he was invited by Duke Friedrich Albrecht zu Eulenburg, head of the Eulenburg Expedition who was in Japan to negotiate a trade treaty between Prussia and Japan. The Duke had asked Harris to use Henry as an interpreter during the negotiations. When Henry's meeting with the Prussian envoy was finished, he left for the consulate around nine o’clock in the evening. He was accompanied by three pro-government samurai and four footmen. In 1994, Reinier H. Hesselink made a detailed reconstruction of what happened next. The description also mentions the perpetrators.

What happened was that Henry and his company were attacked by seven so-called 'shishi', political activists who were in favor of the shogun and against foreign interference. The word shishi literally translates to 'men with a high purpose'. Many of these men were impoverished and because of this capable of anything.

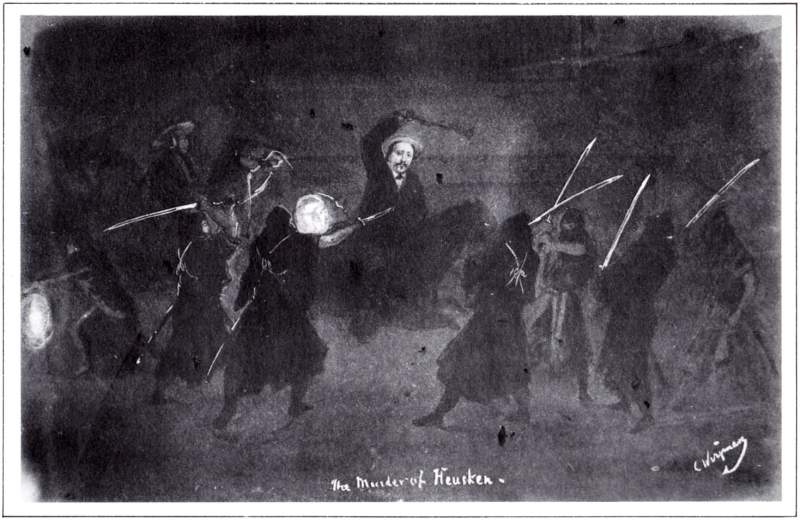

The Murder of Heusken (source: Yomigaeru Bakumatsu, public domain)

The Murder of Heusken (source: Yomigaeru Bakumatsu, public domain)

The attackers were dressed entirely in black and the usual security nearby was absent that night. No one was present at a bridge normally guarded by the local clan. The attackers were on the bridge in an ambush.. The procession with Henry was preceded by two stable hands on foot with lanterns. Behind them, the samurai Suzuki Zennojō rode on horseback to lead the group. Then came Henry on his horse with two stable hands on foot on either side. At the back were the two other samurai, Ajima Kōkichi and Kondō Naosaburō. As soon as the attackers heard the horses coming, they came out of their ambush with swords drawn. First, the stable hands were taken out with their lanterns. Zennojō's horse was stopped with a hefty sword blow. The other two escorts immediately took off. Almost at the same time, Henry was attacked by two man. He was able to dodge one of the swords, but from the other side he was seriously hit in the abdomen. At the same time Henry gave his horse the tracks, while from the other side came another sword blow. At first he had the idea he had come off well, it quickly passed when he felt severe pain. After about 200 meters he ordered his servant to stop the horse and help him off.

The entire attack had lasted only a few seconds and both attackers had only struck once each. Except for Henry, none of the others were hurt. He was lying wounded in the street with his servant next to him. Zennojō had driven on under the assumption that Henry was following. When he realized that his horse was severely wounded, he continued on foot to get help. The other samurai later told that they had stayed with Henry all along, but in his final hours Henry was able to tell that he had been lying alone on the street for at least half an hour. When no help came, Henry sent his servant to Robert Lucius, the doctor at the Prussian Embassy. All the time, blood was pouring out of his abdominal wound.

Eventually, help came for Henry. The samurai had found a Japanese doctor and also residents from the neighborhood dared to come out and see what was going on, because Henry had been screaming in pain. Lying on a door, Henry was taken to the Zenpuku-ji temple. Around 9:30 p.m., the company arrived at the temple. There, Henry himself was able to tell Harris what had happened. Harris immediately sent a messenger to the Prussian Embassy. Doctor Lucius, who arrived later, could do little but watch Henry Henry eventually die. The doctor's report states that he died just after midnight, 16 January. A French priest had assisted Henry in his last hour.

After Henry's death

It became clear that Henry had died from blood loss caused by a severe wound in the abdominal cavity and a slight wound to the upper body and upper arm. The bleeding had been unstoppable, but the chances of him surviving were slim at the time. An infection of injured intestines would have eventually killed him. The fact that he bled to death saved Henry a lot of pain. The nature of the wound also indicated that the attackers had wanted to kill him immediately.

Less than an hour after Henry's death, Harris received a visit from Oguri Bungo no Kami, a senior State Department official. He deeply regretted Henry's death, something that was considered quite unusual for a Japanese official. After the governor saw Henry's body, he swore that no effort would be spared to find the killers.

Soon, rumors began circulating among the foreign community that the shogunate was responsible for the attack. Japanese themselves suspected the wandering samurai or the followers of a disgruntled ruler. Tokyo was full of men like this, especially since Japan had opened up to the West. These men felt the end of Japan's isolation as a great humiliation. They had lost everything without a fight, and they saw men like Henry as the enemy. Henry's behavior in particular seemed to have challenge them, something he may not have been fully aware of or he didn't want to see. The whole politics behind Japan's opening eluded to the shishi, their main goal was to save their country. The perpetrators turned out to be among them.

Henry left behind a Japanese wife and a young son. Little is known about them.

The funeral and political consequences

From a letter from Harris to Henry's mother, we know how the funeral went. It took place on 18 January and the procession was extensive, just as Harris would have liked. The demonstrative large funeral procession consisted of many dignitaries from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, a flag parade, the march band of the Prussian frigate Arcona and many other foreign representatives. In the middle of the procession the body Henry was covered with the American flag and accompanied by eight Dutch marines.

The funeral took place at the cemetery near the Korin-ji temple which was not far from the consulate at the time. Immediately after the funeral, most Western diplomats left Tokyo. They went to the city of Yokohama where it was relatively quiet. For their protection, more French and English soldiers were brought ashore. Henry's murder proved to have a negative effect on the US-Japan relations. Especially since no one was still convicted of the murder. All the Japanese government did was pay compensation to Henry's mother.

The chaotic period in Japan that Henry fell victim to finally came to an end in 1868, when the emperor was elected leader of the country and the Meiji period began. But Henry was not the last victim of what would be known as the Bakumatsu, or the transition from the shogunate to the empire. In 1862, the British merchant Charles Richardson became a victim of the samurai. Richardson was killed near Yokohama in 1862. In 1868, 11 French sailors were killed in an incident.

Aftermath

The ‘Nieuw Amsterdamsch Handels- en Effectenblad’ reported on 12 February 1862 that Henry's mother had received the aforementioned compensation from the Japanese Government. The amount of this compensation was reportedly 10,000 US dollars. The compensation was made possible thanks to Towsend Harris. On 2 April 1862, Henry's mother wrote back a thank you letter to Harris. The letter was later found among Harris' belongings. In her letter, Mrs Heusken thanked Harris in detail for receiving the sum and also for Harris having a monument to her son erected. Mrs Heusken has benefited from the compensation for a few years. She died on 12 February 1888, at the age of almost 83.

The perpetrators

The shogunate with its extensive police apparatus, however, failed to find the perpetrators. Harris heard strong words from dignitaries over and over again, but no one was arrested. However, the interrogations of Henry's escorts had already revealed a suspicion, based on the rallying cry of the attackers. Presumably they were from Satsuma, in southern Japan. A diary fragment of a young samurai from Satsuma makes it even more clear who was involved, but this may be based on gossip because at the time he wrote this, the writer was not in Tokyo. The men named are Masumitsu Shinpachiro (1841-1868) and Imuta Shohei (1832-1868). The latter would have inflicted the massive abdominal wound on Henry. All the men mentioned in the journal did not survive the turbulent times. Some of them later committed suicide to save their honor. Further research made it clear that these men belonged to the Kobi no kai (Association of the Tiger Tail). This was a group of men who had exchanged loyalty for a master for loyalty to Japan and were not afraid to 'step on the tiger's tail'. Behind this group was the samurai Kiyokawa Hachiro (1830-1863) who went his own way and was able to get money where no one else could. In front of other groups with the same ideals, Kiyokawa tried to make a name for it. He already realized that the shogunate did not have sufficient response to attacks by shishi. Kiyokawa was the one behind the plan to kill Henry. After the murder, he would have even bragged about it.

The shogunate arrested several members of the Kobi no kai and interrogated them intensely. It must have become clear who the perpetrators were. Kiyokawa had fled by now. However, he was lucky to assemble a small army and he went to Tokyo where he wanted to put his men in the service of the shogunate to keep foreigners out. The shogunate initially gave Kiyokawa the power to act with his army, but in 1863 he was assassinated by supporters of the shogunate who had a different course in mind. Supporters of Kiyokawa then managed to secure themselves and gave him a proper burial.

Henry's tomb monument

Henry was buried in the cemetery of the Korin-ji temple, a Rinzai Zen Buddhist temple in Azabu, not far from Zenpuku-ji. At first, a simple grave was given to Henry that was rather hard to find. Therefore, at the beginning of the twentieth century, an attempt was made to make a more appropriate tombstone for Henry. That succeeded and on 30 May 1917, the American Memorial Day, the new monument was inaugurated with a small ceremony. The stone shows the following under an image of a cross:

SACRED

to the Memory of

HENRY C.J. HEUSKEN

Interpreter to the

AMERICAN LEGATION

in Japan

BORN AT AMSTERDAM

January 20, 1832

DIED AT YEDO

January 16, 1861.

The now weathered tombstone consists of a stepped basement with a rectangular high column on which the said text is embeated on the front. The column is covered by a wide basalt stone cover. This cover resembles that of older Japanese tomb monuments but is somewhat more detailed and features an ornament at the front. All the way on top is an onion-shaped ornament. Here and there you can see traces of a restoration, in which cement has been used, among other things. The entire monument looks constructively good. At the monument there is always a bottle of gin, left by visitors. Every year, around the anniversary of Heusken's death, a ceremony is held at the grave monument by the Dead Dutchman Society.

Grafmonument Heusken in 2016 (photo author)

Grafmonument Heusken in 2016 (photo author)

For those looking for the monument, it can be found on the temple grounds via a narrow path on the right side of the temple. The grave is on the large grave box at the back right, on the last row against a wall of large stone blocks.

The address of the temple:

Korin-ji Temple

4/11/25 Minami Azabu

Tokyo

Literature

- The complete journal of Townsend Harris, first American consul general and minister to Japan, Japan Society, New York 1930

- Hesselink, Reinier; 'The Assassination of Henry Heusken' in: Monumenta Nipponica vintage 49, number 3, 1994 (pages 331–351)

- Heusken, Henry; Japan Journal 1855-1861, translated and edited by Jeannette C. van der Corput and Robert A. Wilson, New Jersey 1964

Internet

- https://www.flickr.com/photos/rekishinotabi/9246497637

- Two Famous Murders in My Neighborhood (part 1) https://markystar.wordpress.com/2013/04/02/two-famous-murders-in-my-neighborhood-part-1/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Heusken

Thanks to Geoffrey Tudor and Willem Kortekaas of the Dead Dutchman Society

- Last updated on .