Willemstad – Jewish cemetery Beth Haim

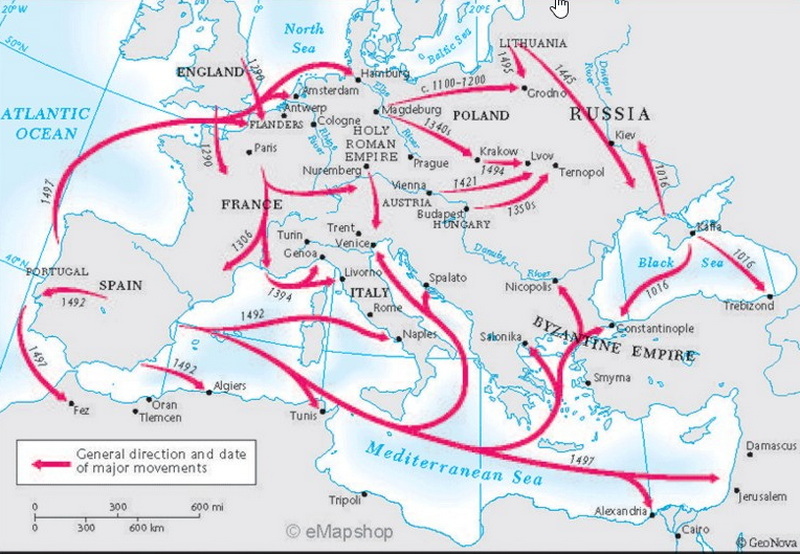

The diaspora of Jews living in the Iberian Peninsula caused quite a stir, especially in the New World. The expulsion was the result of the Spanish Inquisition established in 1478. Ever since the Moorish rulers were defeated in Spain, the Catholics had forced the remaining Moors and Jews to convert to Christianity. One of the consequences of the Inquisition was that over a longer period of time around 160,000 Jews fled the country. Many moved to Portugal, but the Inquisition ruled there too, causing many Jews to move further along. Those who stayed were forced to convert. Jews who converted were called 'new Christians' or 'conversos', which means as much as converted. The expulsions reached a peak in 1492 and 1497.

Overview of Jewish migration and expulsions between the year 1000 and 1500 (https://www.jewishwikipedia.info/diagrams.html).

Overview of Jewish migration and expulsions between the year 1000 and 1500 (https://www.jewishwikipedia.info/diagrams.html).

Fate of the conversos

Although many Jews initially converted, in the long run they had no other choice but to leave. Although there was no mention of conversos in edicts of expulsion, they were nevertheless subject to various restrictions. This was due to the idea that as long as there were unconverted Jews in the country, these conversos were influenced by them. The edicts of 1492 and 1497 were therefore specifically aimed at unconverted Jews. Of the Jews who fled, some returned to Spain and converted to Catholicism. This conversion was partly prompted by the hardships experienced elsewhere.

The conversos in Spain and Portugal were also called marans, after the Spanish word marrano which means scumbag or pig. Although the use of the word was banned numerous times, the name lives on to this day. Jews simply chose to convert in order to be part of everyday life. Numerous conversos managed to obtain high public and ecclesiastical positions in the first half of the fifteenth century. This eventually led to disturbances and measures to exclude conversos from high positions. This eventually led to the establishment of the Inquisition to find out whether someone was of the true faith.

Ultimately, the balance tipped in favour of those who had the means to flee. Those who had no money converted and faded into obscurity. A small part continued to celebrate the Jewish cult in secret in anticipation of better times. With the departure of many Jews and the conversion of the rest, the funerary cult that the Jews had brought with them to the Iberian Peninsula from the second century onwards disappeared. Synagogues, cemeteries, and other buildings that reminded us of the Jews were razed to the ground in the decades that followed.

In the Spanish city of Utrera, the remains of a synagogue from the fourteenth century were found in 2023. This was first used as a church and later as a restaurant and disco (photo Utrera city hall).

In the Spanish city of Utrera, the remains of a synagogue from the fourteenth century were found in 2023. This was first used as a church and later as a restaurant and disco (photo Utrera city hall).

On the run

For many Jews, fleeing abroad eventually proved to be the solution. From the end of the fifteenth century, the Jews spread across the Ottoman Empire and various Western European countries. The cities on the North African and Moroccan coasts were also a refuge. Jews kept in touch with each other and were held together by a trade network through which they achieved a certain prosperity. These prosperous communities increasingly attracted from the Iberian Peninsula Jews who had remained behind. Trade also brought Jews to the Americas, where colonies were founded in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries by nations that were friendly to the Jews. These nations also offered opportunities to continue trade regardless, and one of those possibilities was the conquest of Curaçao by the Dutch West India Company (WIC).

First exodus to the Americas

At the invitation of the WIC, Jews from Amsterdam also ended up in Curaçao. Later, they were joined by Jews from the colonies in South America. The changing rulers of those colonies did not provide a calm, stable environment for the Jews, but under the WIC the Jews could continue to trade with the Spanish and Portuguese colonies. Founded in 1624, the WIC was an attractive organisation for the ever-growing Sephardic community in Amsterdam. The WIC supplied the ships and, with its own bankers and slave trade as the engine to perform the hard labour, countless products from the Americas were brought to Europe, where Amsterdam was an important centre. Curaçao would grow to become one of the most important places for trade by the Jewish community. Suriname, on the other hand, was mainly a country for the production of sugar and coffee.

Jews in Curaçao

In 1499, the first European, a Spaniard, set foot on Curaçao. The population of the island could not withstand the attacks of the Spaniards and the island was occupied, just like Aruba and Bonaire. Almost all of the island’s inhabitants were enslaved and transported away. Those who stayed behind had to convert to Christianity. In 1634, the WIC attacked the island and the Spaniards surrendered. The aim of the WIC was to have a base for privateering and trade. Most of the Spaniards and indigenous inhabitants were subsequently transferred to the Venezuelan coast.

In 1648, the WIC invited colonists to settle in Curaçao. Several Sephardic Jews, such as João de Yllán and in 1652 also David Cohen Nassy, were given permission to settle in Curaçao with the promise that they would attract more colonists and grow products that were in great demand. The intention was that the colonists would turn the land ceded to them into plantations. Nassy ultimately did not take advantage of the invitation, but became active in Suriname. There, in 1654, many Jews from the lost colony in Brazil joined the community. They had been able to take little with them from Recife where most of them had lived, but they had been able to take their trade contacts. A few of that group from Brazil also ended up in Curaçao, but in 1659- 70 Jewish colonists from Amsterdam arrived in Curaçao under the leadership of Isaac da Costa.

The plantations did not amount to much l, but trade did. The Jews travelled a lot to Venezuela for this purpose, but also to other islands or cities where a Jewish community existed. The Jews had also managed to secure an important role in the trade in much-needed labour : enslaved people from Africa were transported via Curaçao to nearby Spanish colonies. The WIC ensured a constant supply, making the island very attractive to traders. For other merchandise, the Jewish merchants on Curaçao maintained close contacts with cities such as Amsterdam, Middelburg, and Rotterdam. In addition, there were also contacts with the plantations that had been established in Suriname. Curaçao was also the springboard for the formation of the Jewish community in America.

The first cemetery and expansions

On one of the plantations north of the Schottegat, called Bleinheim, a cemetery was built. The cemetery, Beth Haim, house of life, was located at an altitude of about 9 meters above sea level, leaving the original landscape with its undulations intact. The soil consisted of old volcanic rock, diabase, with a layer of calcareous rock or old coral formations above it. The oldest part of the cemetery probably dates from 1659. Here, in a bend in the wall, lies the old entrance. However, the oldest stone dates from 1668 and is a baked tile for Judith Nunes de Fonseca. The stone was found during repair work and has been transferred to another location in the cemetery. The lack of older grave monuments has numerous reasons, including decay of the tombstone or destruction during the construction of other graves. It does not rule out the possibility that older graves are present.

In 1726, an expansion was built to the south and on a narrower strip to the east of the original cemetery. In the same year, the Rodeamentos House was also built at a new entrance on the south side. This house of procession, as it is literally translated, is the place where the body of the deceased is prepared for burial and where the next of kin walk seven times around the coffin of a male deceased. The entrance on the south side had a logical reason because most of the dead were brought in by by water from Willemstad. The distinction between the original part and the expansion was expressed in the names Beth Heim velho (old cemetery) and Beth Haim novo (new cemetery).

In some cases, existing graves were desecrated, although that was actually against the rules. The desire to be buried next to a loved one was sometimes greater, which meant that graves that had not received a stone were easily desecrated. Where a tombstone was placed on the grave, it was always in the same way, although there are exceptions. The current brick tombs, plastered with mortar made on site, were only installed in the thirties of the twentieth century because many tombstones were subsiding. With several tombstones in a row, a continuous system was made so that the graves were placed in blocks together with the tombstones on top of them. Among the funerary monuments there are also a number of low tombs with a semicircular shape. According to some, these grave monuments are among the oldest in the cemetery, made from the material that was available on location. To what extent this is true is not clear. We do sometimes find this form in other Jewish cemeteries, but not everywhere.

Various types of tombs on the edge between the old part and a later extension of the cemetery.

Various types of tombs on the edge between the old part and a later extension of the cemetery.

In the successive parts of the cemetery, we see a development, where, for example, in the nineteenth century there were also rounded tombs, but also obelisks, pedestals with vases, and columns with flames. Classic stelae also occur occasionally, sometimes richly decorated with symbols. Even an occasional table tombstone is not missing.

In 1750 an expansion pan followed on the east side with a narrow strip of five rows of graves. Not that it was necessary, but a difference of opinion within the Jewish community led to the new group claiming their own part of the cemetery. After the difference of opinion was settled, the separate part was added to the existing cemetery. In 1800 a much larger expansion followed in which the northern part was added and also the southwest corner. Finally, in 1822, a small expansion followed in a protrusion on the southeast side, against the ridge that lies here. This part was also due to a difference of opinion, and this was also added to the cemetery after the conflict had been settled. This brought the cemetery to a size of more than 11,000 m2, completely walled.

In 1856, the 'Cazinha dos Cohanim' was built to the right of the Rodeamentos House. This building allows the kohanim, descendants of the priestly caste, to attend a funeral of a relative without entering the cemetery. After all, they are not allowed to enter a cemetery because they would become unclean.

The Rodeamentos House and the 'Cazinha dos Cohanim' with a small part of the last extension on the left.

The Rodeamentos House and the 'Cazinha dos Cohanim' with a small part of the last extension on the left.

As early as 1841, the Jewish community had requested the governor for additional land to enlarge the cemetery. To this end, a piece of land on the De Hoop plantation, which was then owned by the government, had to be acquired. For various reasons, it was not until 1879 that the 1,300 m2 were added to the cemetery. However, the section has never been used as such due to other developments but was also never built on or used by the adjacent refinery.

Materials and symbols used

While in some places in the cemetery there seem to be no graves, the graves of the poorer Jews can probably be found there. Those who could afford it had Belgian Blue stone or marble tombstones, or other forms brought over from the Netherlands or even Italy. Although marble certainly stands out, there is also a lot of bluestone to be found in the cemetery, as we also know from Jewish cemeteries in the Netherlands and Suriname. Sometimes the ridges on the side are weathered and the underlying brick is visible. In some younger, twentieth-century grave monuments, tiled floors have been laid around the monument and even diabase has been used occasionally. It is clearly visible that marble came in different qualities and that it was not always resistant to the weather conditions on the island.

The choice of symbolism sometimes seems very Christian. Moreover, we come across symbols that we generally do not encounter in Jewish cemeteries in the Netherlands. For example, there is a classical base over two graves with different representations of angels mourning by a veiled urn, pouring water over a torch or resting by a vase. The angels all have a torch pointing downwards in their hands. Angels may not be worshipped in Judaism, but they can be invoked for protection. The depiction of angels is not common, but they do play a major role in faith. The funerary monument is for Abraham de Jacob Jesurun and his wife Esther. The latter died in 1846 and only then was the monument erected, imported from Genoa.

There are also more intimate scenes, such as on the tombstone for Ester Alvares Correa (died 1794), wife of Benjamin Vaz Farro. Her tombstone depicts a woman breastfeeding her child. The image reflects the immense loss that the family must have felt at the death of their mother. The stone is made of marble, and the image has now lost much of its fine detailing as a result of weathering.

In some marble tombstones, the weathering is so great that nothing remains of text or images.

In some marble tombstones, the weathering is so great that nothing remains of text or images.

On some tombstones, nothing remains of the text, but the symbol is still visible, such as a skull with bones or a scene from the Old Testament. Very recognisable symbols such as winged hourglasses, blessing hands or birds also occur. A number of ship captains chose the image of a ship on their tombstone. The axe is also often placed on the (palm) tree. A representation that refers to the life that was abruptly ended. Sometimes only a branch is cut off, referring to the remaining family that has to miss a member.

In addition to Hebrew, Portuguese is often the official language on the stones. In addition, Spanish, English and some Dutch are present. It also shows the diversity of the Jewish community on the island and reveals something of their trade network where speaking multiple languages was of great importance.

Second Jewish cemetery

In Europe, Amsterdam began to lose its appeal to Sephardic Jews in the eighteenth century. They looked for better prospects in cities such as London, Bordeaux, and other French ports. Quite a bit also changed for Curaçao. A slave uprising in 1795 turned the island upside down and in the early nineteenth century two British occupations followed. Political and economic unrest in the Spanish (former) colonies led to an economic depression. Many Sephardic Jews on Curaçao sought better prospects on other islands in the Caribbean or in Venezuela and Columbia. As a result, the number of Jews on the island decreased from 1,200 in 1785 to 785 in 1850. To a small extent, American cities such as New York, Philadelphia or Newport turned out to be more interesting. In the meantime, Dutch power in the Caribbean diminished considerably and the networks of the Sephardic traders, which were so intertwined with those of the Portuguese and Spanish, could no longer withstand the British and French takeover of the maritime trade.

When in 1864 a part of the Jewish community broke with traditional values, they built a liberal synagogue and had their own cemetery built near Willemstad. This cemetery, located in Berg Altena, was still outside the built-up area at the time, but within walking distance of Scharloo where many Jews lived. The cemetery was located between a Protestant cemetery to the west and a Roman Catholic cemetery to the east.

Not only was this cemetery more accessible, but it also took on a different appearance than the old cemetery. When in 1880 taxes were imposed on the Jews for transportation of their dead, the Orthodox Jews decided to buy a piece of land next to the liberal cemetery. A wall separated the two parts, but it was demolished in 1958 and in 1964 the two municipalities were merged together again.

Beth Haïm in the twentieth century

While the two Jewish communities on the island buried their dead separately from each other from 1880 onwards, the old cemetery also remained in use. There were still graves available and often family members wanted to be buried close to their loved ones.

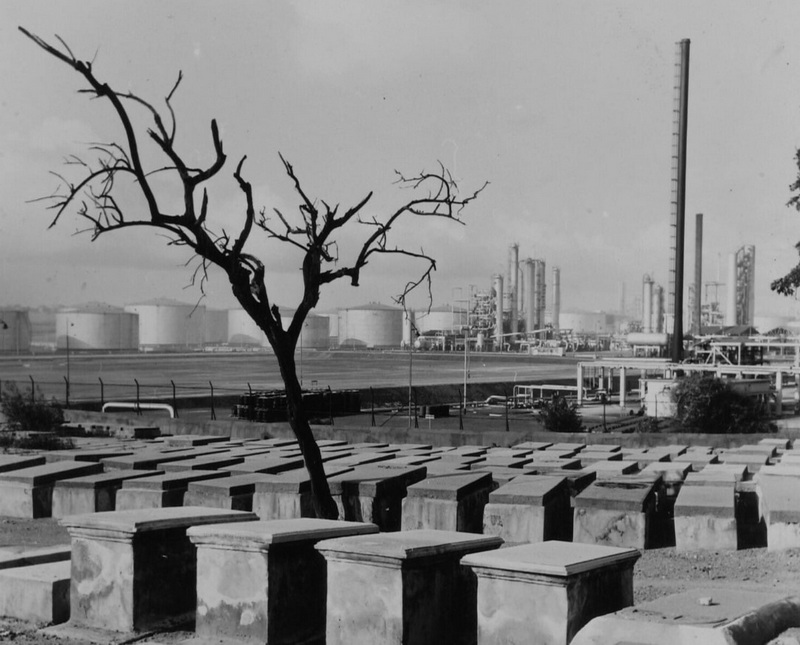

In 1912, the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company, later Shell, acquired a concession to search for oil in Venezuela. The proceeds were initially modest and only a warehouse was built in Curaçao. After production increased, Shell decided to build a refinery. Not in Venezuela, but strategically located in Curaçao, which had a stable administration and was easily accessible for large seagoing vessels. The construction of the refinery took place on a peninsula in one of the bays of the Schottegat. Several plantations were sold and the refinery expanded to the boundaries of the Jewish cemetery. Soon the refinery was the largest in the world. A lot of employment was created, but at the same time the refinery depleted the groundwater, making agriculture in Curaçao more difficult. The refinery proved to be disastrous for the cemetery with its emissions of sulfur and other toxic substances. The marble weathered faster due to the emissions and the appearance of the cemetery was strongly affected.

A photo from 1964 that appeals to the imagination with the refinery in the background

A photo from 1964 that appeals to the imagination with the refinery in the background

(Wereldmuseum Collection, TM-20003995).

In the meantime, more and more Ashkenazi Jews arrived in Curaçao and eventually got their own synagogue. However, burials were made in the same cemeteries. Until 1955 there was no separate section for Ashkenazim. Eventually, the number of Jewish inhabitants of the island continued to decline, mainly due to the deteriorating economic situation in Curaçao. Many families moved to South American and Caribbean countries. After 1960, young people in particular became interested in the United States to a certain extent to study. Miami and New York were preferred.

Importance of Rabbi Emmanuel

In the twentieth century, Isaac S. Emmanuel (1899-1972) published a survey of the valuable stones of the cemetery. Emmanuel was born in Thessaloniki, Greece as the son of a rabbi. He himself also became a rabbi and also a historian who, among other things, published an important work on the Jewish cemetery in Thessaloniki in 1925. This is important because in World War II the cemetery was completely destroyed by Greeks and Germans. Emmanuel became a rabbi with the Jewish community in Curaçao in 1936 and while living on the island, he documented the more than 2,500 tombstones in the old cemetery and mapped their location. Not every grave still has a stone to be found, as there are an estimated 6,000 graves on the site. In 2001, in recognition of his work, the road leading to the cemetery was named after Dr. Isaac Emmanuel.

One of the funerary monuments mapped by Immanuel, a bluestone tombstone.

One of the funerary monuments mapped by Immanuel, a bluestone tombstone.

Preservation of the cemetery

A round of restoration in 1930 was mainly focused on tidying up the cemetery and the tombstones. In the mid-twentieth century, it became clear that many grave monuments were deteriorating rapidly. The Jewish community regularly corresponded with the owners of the refinery about the cause. The owners of the refinery saw no link between the decay and the emission of toxic substances from their factory. However, they did want to contribute to the preservation of cultural heritage. For their part, the Jewish community did not have the resources to conduct extensive research into the decay. When single-handed attempts to stop the decay did not work, in 1959 the Russian architect and sculptor Serge Alexeenko was commissioned to make a replica of eight funerary monuments in order to at least preserve something. The stones are still in the Jewish Cultural Museum in Willemstad. Alexeenko was an interior designer who obtained Dutch citizenship in 1948. In Curaçao he designed, among other things, the church in Soto and Santa Rosa. He also restored numerous country houses on the island in the 1950s and 1960s..

In 1960, Shell, the owner of the refinery, suggested that the cemetery could be moved. Obviously, this was not a solution, but Shell did respond that they had done a lot since 1957 to reduce the pollution of the refinery, including building higher chimneys and improving processes. But at the same time, the company felt that they had contributed enough without declaring that the damage was due to them. In the meantime, Shell was paying for a special coating for the stones. Another attempt in the 1960s with a formula by a New York professor proved to be unsuccessful. In the nineties of the twentieth century, J. Querido of the then National Service for the Preservation of Monuments in the Netherlands conducted research into the weathering of the stones. No decisive conclusion was made about the cause. However, further research was advised, but the Jewish community did not have the resources for this. In this century, several attempts at restoration were made, but without any significant results. An attempt to make more replicas of the stones with synthetic material also came to nothing because the material decayed within five to seven years.

Immediately in the sixties, the 8 replicas in the Jewish Cultural Historical Museum in Willemstad were admired by visitors (Jewish Historical Museum. Image id CW-NAC-0009171).

Immediately in the sixties, the 8 replicas in the Jewish Cultural Historical Museum in Willemstad were admired by visitors (Jewish Historical Museum. Image id CW-NAC-0009171).

In the meantime, much more archival research has been done and the grave monuments are better documented. You can also take a virtual walk around the cemetery online via the Beth Haim Blenheim website. And the maintenance of the cemetery still requires a lot of resources from the dwindling Jewish community. Despite the fact that similar cemeteries in the Netherlands and Suriname are now protected heritage, the one in Curaçao is not.

Thanks to: Ronald Gomes Cassères, author and historian

Internet:

- The Beth Haims of Curaçao: https://bethhaimcuracao.org

- Joodse graven vergaan in zwaveldampen: https://caribischnetwerk.ntr.nl/2016/05/04/joodse-graven-vergaan-in-zwaveldampen/

Literature

- Cohen, Julie-Marthe (red.); Joden in de Cariben, Zutphen 2015

- Emmanuel, I.S.; Het oude Joodsche kerkhof op Curaçao, overdruk uit Maandblad “Lux” van jan-febr. 1944 – No. 4

- Emmanuel, Isaac S.; Precious stones of the Jews of Curaçao, Curaçaon Jewry 1656-1957, New York 1957

- Gomes Casseres, Ronald; A tale of Two Jewish Cemeteries: Preservation of Jewish Historic Heritage in the Carribbean, in: American Jewish History, Volume 107 – Numbers 2 /3 – April / July 2023.

- Huisman, P.H.; Sefardiem. De stenen spreken / Speaking stones, 1983

- Ditzhuijzen, Jeanette van; Geschiedenis in steen. De ontwikkeling van de monumentenzorg op Curaçao, Amsterdam

- Gibbes, F.E.; Restoration efforts for the “speaking stones” of the Beth Haim cemetery, September 2013

- Last updated on .