Early Dutch Cemeteries II - Outside New Amsterdam

Outside the ever-growing city of New York, many more cemeteries were established in the course of the eighteenth century. Many of those cemeteries were built on the outskirts of the city, but they often quickly overtook such a place. The Dutch church grew rapidly in New York and soon needed more churches.

For example, in 1729 the Middle Dutch Church was inaugurated with a cemetery around it. The church was about 200 yards north of the church on Garden Street. The graveyard was used for a little less than a century. In 1823, burials were no longer allowed. Entire parts of the cemetery then disappeared due to street widening until everything was cleared up in 1844. Today there is a large bank building on the site. The North Dutch Church was built in 1768, along with a graveyard. This also had to be closed in 1823 and in 1866 the land was rented out. In 1875 the congregation was dissolved. This is how it went with more denominations and therefore also with the cemeteries. Some of New York City's earliest cemeteries still exist, including Jewish ones. There is virtually nothing to be found of Dutch traces in those places. Many originally Dutch families had already moved to the rural part of Manhattan or to Long Island in the seventeenth century.

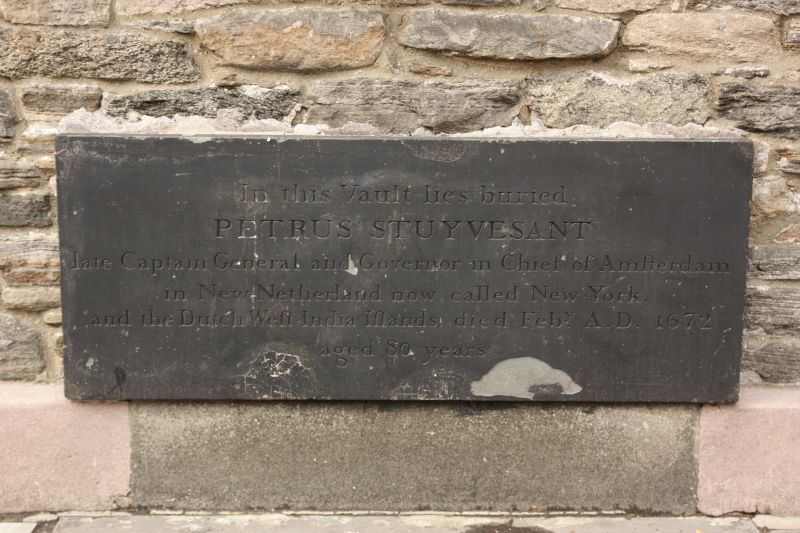

USA 013 Peter Stuyvesant tombstone (photo Leon Bok, 2009)

USA 013 Peter Stuyvesant tombstone (photo Leon Bok, 2009)

Worthy of mention in Manhattan is of course the burial place of Peter Stuyvesant (1611-1672), the last governor of New Netherland. He had a chapel built on his bowery [1] in 1660, where he was also buried in a burial vault in 1672. In 1793, a great-grandchild donated the grounds of the dilapidated chapel to the Episcopal Church on the condition that a new church be built. It was completed in 1795, dedicated to St. Mark. Today there is not much more to see than an entrance to the cellar where Stuyvesant was buried. The accompanying cemetery is unfortunately made rather 'neat' and not very original anymore.

Still under the rule of the WIC, many new settlements were founded outside of New Amsterdam with mainly Dutch residents, such as on Manhattan, Staaten Eylandt (now Staten Island), 't Lange Eylandt (now Long Island) and in the Hudson Valley. Those villages arose after the population increased sharply. Around 1630 there were about 300 Dutch people in the area. That number had grown to about 3,000 fifteen years later. The growth meant that new settlements were set up. The number of non-native speakers in the colony also grew strongly, mainly due to English newcomers. They founded places like Vlissingen, Heemstede and Middelburgh. These villages may have had a Dutch name, but the majority of the population did not speak a word of Dutch. Nieuw-Amsterdam and Beverwijck remained the largest towns in the colony for a long time. The villages mentioned below had an average of 100 to 200 inhabitants at the end of the seventeenth century. When the British took over, about 10,000 people lived in the entire colony.

Manhattan

Outside of New Amsterdam, a few more villages were founded on the island of Manhattan. The island is just over 20 kilometers long and its widest point measures almost 4 kilometers. Of the total area of 59 square kilometers, New Amsterdam occupied only a small part in the extreme south. New Haarlem was founded in 1658 in the north of the island. The church was built in 1667 and people could also be buried there. During the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) the church was destroyed, but rebuilt on the same spot. Funerary vaults were also built at that time. In 1881 a new church was built elsewhere and parts of the land were sold. The remains of the cemetery and burial vaults were transferred to Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

Noortwijck or Greenwijck was founded on the west side of Manhattan, just above New Amsterdam. This small hamlet was not given a church and its own cemetery until the beginning of the nineteenth century. It disappeared a century later for the construction of 7th Avenue. A little further north, now on the west side of Central Park, was the Harsenville district with the village of Bloemendaal. Harsenville was named after a Dutch farmer who owned land here and who founded the Bloomingdale Reformed Dutch Church in 1805. Burials were also held here from 1809, but had to be discontinued in 1851. That wasn't because the cemetery was full, but because the city then banned burials south of 86th Street. The church community was dissolved in 1913. The church, already the third of the community, was demolished.

Excavation at the Dyckman-Nagle cemetery in 1926. The city is already close to the abandoned cemetery (Copyright Dyckman Collection)

Excavation at the Dyckman-Nagle cemetery in 1926. The city is already close to the abandoned cemetery (Copyright Dyckman Collection)

In the meantime, cemeteries were not only built at churches. Often a family cemetery was established at their own farm, on their own land. In Manhattan there were only a few, such as the Kip family cemetery and the Dyckman-Nagle family cemetery. The first was already cleaned up in the mid-nineteenth century, while that of the Dyckman family lasted a little longer. Their cemetery was established on their own land that shared with the Nagel family. Both families owned the land north of today's 190th Street as early as the 17th century and built their farms here. Their land was about 150 hectares, but much of it was rocky and unsuitable for agriculture. The Dyckmans' farm was destroyed during the American Revolution and a new home was built along Kings Highway (now Broadway), which ran across their land. Located slightly to the north, between today's 212th and 213th Streets, the cemetery was believed to have been used by the family for a long time. Later, other families were also buried there. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century it became clear that this area would also be built on. At the turn of the century, the Dyckman family had the remains of their loved ones transferred to Oakland Cemetery in Yonkers. In 1926 the last remains were transferred by the municipality to Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx. At that time, part of the site was already built up with apartment buildings. Photos of the excavation are known and some of the dead were also identified. A total of 417 corpses were transferred. Little is known about the surviving tombstones, mainly from the nineteenth century. Of the few family cemeteries in Manhattan, only the burial vault of Peter Stuyvesant remains.

Long Island

East of Manhattan lay an elongated island that the Dutch called 't Lange Eylandt ('the long island'). The land was hilly, but very fertile. In the west of the island, close to New Amsterdam, several villages were set up in the mid-seventeenth century with the permission of Governor Stuyvesant. Those villages were respectively:

- Gravesende (Gravesend), founded in 1645

- Vlissingen (Flushing), founded in 1645

- Breukelen (Brooklyn), founded in 1646

- Nieuw Amersfoort (Flatlands), founded in 1647

- Midwout of Vlackebos (Flatbush), founded in 1652

- Middelburgh (Elmhurst), founded in 1652

- Rustdorp (Jamaica), founded in 1656

- Nieuw Utrecht (New Utrecht), founded in 1657

- Boswijck (Bushwick), founded in 1661

Not all villages were set up by Dutch settlers. For example, Gravesende was founded by Lady Moody, an Englishwoman who had come to New Netherland from the English colony because of her deviant faith. Few Dutch people were involved in the foundation of Boswijck either.

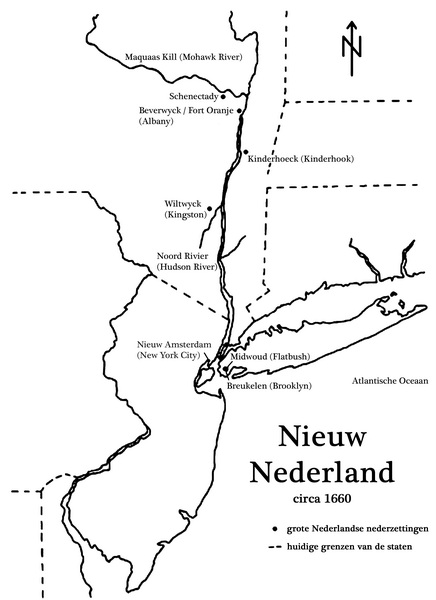

Map of New Netherland around 1660 with the most important settlements from that time.

Map of New Netherland around 1660 with the most important settlements from that time.

Hardly any of the nine individual villages can be recognized in the current city. New York City now consists of five neighborhoods [2] of which Queens and Brooklyn are located on the westernmost part of Long Island. Flushing, Jamaica and Elmhurst are now in Queens and there is little that reminds of the Dutch. A little more of the original Dutch settlements have been preserved in Brooklyn, if only because the coat of arms of the city of Brooklyn bears the motto "Eendracht maackt macht". Now there are about 2.5 million inhabitants in Brooklyn and the city consists of a strict geometric pattern of roads and buildings. As a result, older roads are barely recognizable. Despite the enormous growth of Brooklyn, four of the six original villages still have their old cemeteries.

The old cemetery of Breukelen (Brooklyn) fell out of use in 1849 because burials were no longer allowed. In 1865 the remains and stones were transferred to Green-Wood Cemetery. Not long after, a branch of the clothing store Abraham & Strauss, now Macy's, was built here on Fulton Street. This part of Brooklyn is now called Down Town Brooklyn and is a busy center with shops, government offices and hotels.

One of the gravestones from the old Brooklyn cemetery placed in a circle at Green-Wood Cemetery. (photo Leon Bok, 2009)Also the cemetery at the church of Boswijck (now Bushwick) no longer exists. Burials took place until 1870 and the church was abandoned in 1919. The oldest grave markers were dated 1655. In 1872 all remains, including the markers, were transferred to Cypress Hill Cemetery on the border of Brooklyn and Queens. Witnesses, however, stated that they had seen some grave markers at the site of the cemetery in 1935. The entire area was in any case reissued and built upon after 1872.

One of the gravestones from the old Brooklyn cemetery placed in a circle at Green-Wood Cemetery. (photo Leon Bok, 2009)Also the cemetery at the church of Boswijck (now Bushwick) no longer exists. Burials took place until 1870 and the church was abandoned in 1919. The oldest grave markers were dated 1655. In 1872 all remains, including the markers, were transferred to Cypress Hill Cemetery on the border of Brooklyn and Queens. Witnesses, however, stated that they had seen some grave markers at the site of the cemetery in 1935. The entire area was in any case reissued and built upon after 1872.

Of the four remaining cemeteries, two still have a church that stands on the original site. Those are Flatlands and Flatbush. The church of New Utrecht has been moved and the Dutch church of Gravesend was located elsewhere in the village.

The cemeteries of Flatlands and Flatbush are the most interesting. But that doesn't mean the other two don't deserve attention. Burials took place in Gravesend from ± 1650 and the Dutch Reformed Church of Gravesend chose this place as its burial place after its foundation in 1654. Burial was carried out by the congregation until 1810, after which the ownership of the cemetery was transferred to the municipality. Burials decreased over time until the cemetery came into the hands of the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Unfortunately, the cemetery is closed to visitors. Next to the cemetery is the cemetery of the Van Sicklen family. In the cemetery we find a good number of older grave markers, including some with Dutch text. They date from the second half of the eighteenth century and are made of the typical brown sandstone that was brought from New Jersey.

Burials were probably held in New Utrecht from 1654, while the church was organized in 1677. Until 1826 the church stood in the cemetery, but it was moved to a place where the congregation could be better served. The cemetery remained in use on site and had its own separate section for the enslaved. The cemetery is still used to this day, but only for the burial of urns.

The oldest headstones in the cemetery are all in the English language, but many names are unmistakably of Dutch origin, such as Cortelyou, Van Brunt, Van Pelt and Cowenhoven. The cemetery is maintained by volunteers and was heavily overgrown in 2009 despite their efforts. Compared to the other cemeteries in Brooklyn, that's quite a big difference.

Flatbush, located in the middle of the aforementioned villages, was given a church in 1654 and it will not be long after that for the first time. There were probably also burials in the church, but that is not clear to date. Later renovations showed that there are older graves under the church. But whether that was because they were overbuilt during church expansions or whether there was actually burial in the church, it was not clear. The cemetery was in use until 1913. A striking number of Dutch texts can be found here, which may be because all services in the church here were in Dutch until 1783 and possibly Dutch was still spoken by many afterwards. The oldest stones date from around the middle of the eighteenth century and contain Dutch texts. The oldest English text on the grave marker of someone with a Dutch name dates from 1781. On grave markers of people with a Dutch background who died at an advanced age, Dutch is even more common than with people who died younger. The youngest Dutch text dates from 1807, but after that the texts are all in English.

USA-017. Cemetery of Flatlands with a variety of eighteenth and nineteenth century stelae. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

USA-017. Cemetery of Flatlands with a variety of eighteenth and nineteenth century stelae. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

In Flatlands graveyard, that picture is about the same. The cemetery has been in use since 1663 and also contains a number of funerary monuments with Dutch text. A number of older grave markers have been restored by casting them in a cement 'corset'. In general, the headstones here are in a worse condition than at Flatbush.

In any case, the various old cemeteries have in common that they now lay like a small green oasis in the middle of the busy city.

Along the Hudson

Just like on Manhattan and Long Island, all kinds of small settlements were founded in the Hudson Valley. From New Amsterdam to Fort Oranje (Albany) and even further, new villages were set up in the seventeenth century. So-called patronages appeared throughout the area, large tracts of land owned by a wealthy Dutchman who had the land cultivated by farmers. Rensselaerswijck was such a patronage with its own villages and farms. A patronage often also had its own rules.

As the forts were built along the river, villages and farms often appeared a little further from the river. This was a sort of security measure against incursions by Native Americans who moved easily over water. Those several miles inland gave the villagers just time to prepare for attacks of others. Despite this precaution, settlements were regularly targeted by looting and arson.

One of the larger settlements was Wiltwyck, now called Kingston. This place, about 140 kilometers north of New York, was founded about 1655. The survival of Wiltwyck may have been the result of an uprising not long before. Residents of scattered farms then withdrew to the fortified village. Although people continued to prefer their own farms, Wiltwyck was given the right to exist as a safe place for residents in the area because of the threat from the Native Americans. In 1663 many inhabitants of Wiltwyck were killed in the last uprising of the Native Americans. A year later the name Wiltwyck was changed to Kingston by the English. However, little changed for the Dutch on the spot. They just kept going to their church founded in 1659 and buried their dead in the cemetery near the church. In 1777, the church was destroyed by marauding British, and the cemetery must also have suffered greatly. Nevertheless, there are still quite a few old tombstones in the cemetery today, including some with Dutch text.

In the more northerly Albany, however, it is very different. Albany started around 1618 as Fort Oranje, along the Hudson, set up as a replacement for an earlier fort. Under the WIC Fort Oranje became important as a transit point for the fur trade. The small settlement north of the fort was officially named Beverwyck in 1652. The church had a small cemetery, but the dead before the foundation of this cemetery were buried on a small plot of land near the fortress. Burials were also held in the church, but there was soon too little space. In the current center there was a small cemetery of the Dutch Reformed Church, but it was closed in 1780. A municipal cemetery was established on the edge of the expanding town, but it was also not used for long. In 1801, an even larger cemetery was opened west of Albany. This was used until 1868.

USA-042. Old funerary monuments at the Church Ground at Albany Rural Cemetery. The stelae are laid flat, which does not work well for readability and preservation. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

USA-042. Old funerary monuments at the Church Ground at Albany Rural Cemetery. The stelae are laid flat, which does not work well for readability and preservation. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

Then this cemetery was also overtaken by the buildings. The Albany Rural Cemetery was opened in 1844 and the remains of the old cemetery were then taken to it. The remains of other smaller cemeteries have also been transferred here. That means that today you search in vain for the remains of Dutch graves in the center of Albany. They are all located north of the city, on a nearly 300-acre cemetery. Grave monuments that once stood on the Dutch Church Cemetery can be found on grave field number 49. In any case, they are no longer standing now, because on the so-called “Church Ground” are the hundreds of stones that came over from the older cemeteries, including that of the Dutch Church. Because the stones are in the grass, they are overgrown and barely legible.

Elsewhere in the cemetery is the cemetery of the Schuyler family. It was transferred here in 1920 from Watervliet, where the family had a farm from 1672. Such family cemeteries were, in fact, the most commonly used places for burial of the dead, as we saw with Manhattan. Many of those small cemeteries have since been overgrown, cleaned up or transferred to large municipal cemeteries such as that of the Schuylers. Fortunately, a few cemeteries have been preserved, such as that of the Staats family. Barent Staats bought an island along the Hudson near present-day Castleton at the end of the seventeenth century, which soon got the name Staats Island. The farm here was known as the Hooghe Bergh because of the large hill behind the farm. The family built their own cemetery on the south flank of this hill. Both the farm and the cemetery are still there and the Staats family is still the proud owner. The cemetery is still used. As small as it may be, the history of burials in the Hudson Valley can be seen in a nutshell. From the old, barely worked rough stone to granite, there is an example of all. Unfortunately, many such cemeteries have disappeared.

A number of other smaller settlements along the Hudson did not have their own church and graveyard until the course of the eighteenth century. There are no special funerary monuments to be found there.

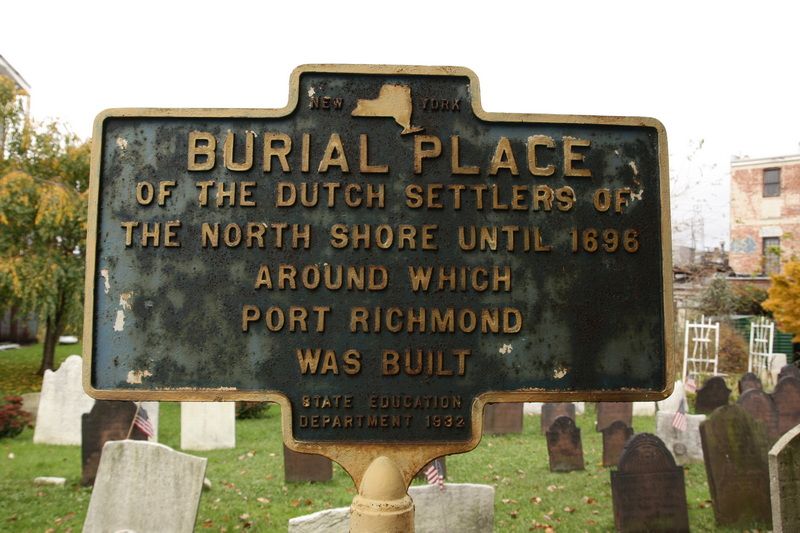

Staaten Eylandt and New Jersey

Compared to Manhattan, Long Island and the Hudson Valley, the Dutch settled relatively late on Staten Island, as the island is now called. This is not due to disinterest on the part of the settlers. They tried several times to gain a foothold on the island from 1639, but each time failed. Attacks by Native Americans caused the settlers to be chased or killed. It was not until 1661 that peace was made with the Native Americans and the first village could be built. That first village was given the name Oude Dorp, now Old Town. Under the English, the island became a county called Richmond, after one of Charles II's sons. In Port Richmond, in the north of the island, the first church was built in 1665. Here was also buried and church and graveyard exist until today. The typical sandstone stelae can be found in the cemetery, but texts in Dutch are not (any longer) to be found, but names such as Van Pelt, Haughwout and De Hart can.

USA-021. Information sign in the Port Richmond Cemetery. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

USA-021. Information sign in the Port Richmond Cemetery. (Photo Leon Bok, 2009)

In the course of the eighteenth century, more and more land to the east was developped and small communities were founded by English and Dutch settlers. Reformed churches were founded in some of the villages, but the Dutch were not part of the majority in this area. As a result, traces of Dutch graves and names are somewhat more difficult to be founde, but some family cemeteries have been preserved. A good example can be found in New Brunswick. There is a small cemetery with some grave markers from the Leydt family from around 1760. The texts are in Dutch and the markers are made of a striking gray sandstone. The shape of the markers resembles that of the brown sandstone stelae from the New York area, but the stone carving shows different shapes, suggesting a more English style was followed.

Thanks to Marieke Leeverink.

Early Dutch Cemeteries I - New Amsterdam • Early Dutch Cemeteries II - Outside New Amsterdam • Early Dutch Cemeteries III - Materials and texts

Notes

- Bouwerij is the name for a farm in New Netherland. The word has been corrupted into Bowery in American. The avenue to Stuyvesant's building in New York still exists and is also called Bowery.

- A borough is a political division originally used in England. The word comes from the Old English word burh, which means fortified city (compare: castle). New York City has five boroughs: Brooklyn, Manhattan, Staten Island, The Bronx and Queens

Literature

- Haacker, Fred C.; Burials in The Dyckman-Nagel Burial Ground, 1954.

- Inskeep, Carolee, The graveyard shift: a family historian's guide to New York City cemeteries, Orem Utah 2000.

- Richards, Brandon Karl; Comparing and Interpreting the Early Dutch and Englisch Gravemarkers of New York’s Lower Hudson Region; 2005.

- Sypher, F.J. (vertaling en bewerking); Liber A. 1628-1700 of the collegiate churches of New York, Grand Rapids (MI) 2009

- Welch, Richard F.; The New York and New Jersey Gravestone Carving Tradition, in Markers IV, 1987 (uitgave van de Association for Gravestone Studies)

- Wieder, F.C. (inleiding en bezorging); De stichting van New York, Zutphen 2009.

Part of this article was delivered in a lecture at Columbia University in New York on October 29, 2009. The research for that lecture and this article was made possible in part by the Netherlands America Foundation (NFA) and supported by Professor Norman Weiss of the Columbia University.

- Last updated on .