Fort Kochi - Johan Adam Cellarius (1740-1796)

When the Oosthuizen, a ship of the Hoorn chamber, leaves the Texel roadstead on 19 May 1762, this also means a definitive farewell to Europe for the man who appears in the pay book as Corporal Jan Adam Zelarius. He was born in 1740 as the son of Johan Jacob Cellarius and Maria Miller from Olm (Ulm), in present-day Germany.[i] Correct spelling of name and place of birth, even if a false identity was given, was important because the salary records were kept in the pay book during the entire service period. That Cellarius was aware of this is apparent from the fact that he wrote a letter to the Hoorn room in which he confirmed the correct spelling of his name and place of birth. A wise decision, because Cellarius had his annual pay statement collected by authorized representatives. In this way, his entire earnings over all those years could be used from Dutch trading houses to invest more than 10,000 guilders in real estate in Ulm (Germany) and in trading contacts in Europe.

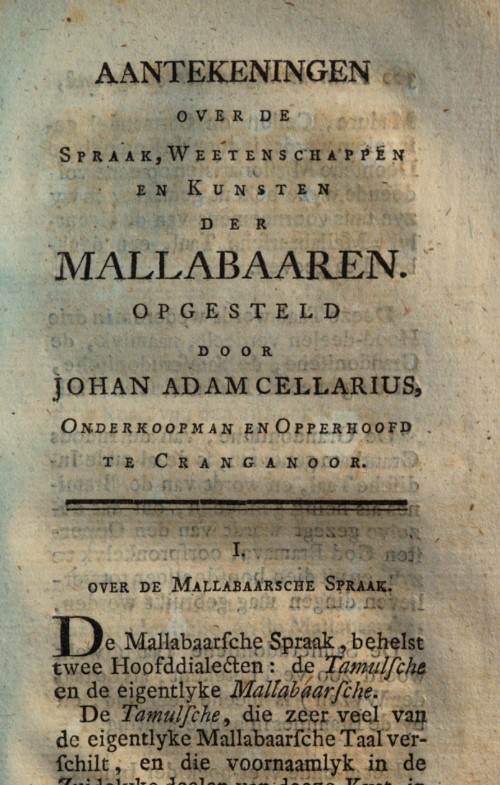

The first years Johan stayed in Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia). He rose from assistant (1764) and bookkeeper (1771) to junior merchant in 1773 and from a monthly income of 14 to 40 guilders in 1775. Somewhere around that time his place of employment also changed and he moved to the coast of Malabar. He must have had all the necessary skills then, because he saw an opportunity to conquer the hand of Maria Catharina Daimichen, daughter of his compatriot Johan Daimichen, who by then had reached the top of the social ladder. They married and had their first son, Johan Adam, baptized on 25 October 1778 in Kochi. Cellarius was promoted to chief, after which the family moved to Cranganoor, where their children Johan Jacob on 23 August 1779 and Maria Helena on 20 August 1780 were baptized. These were years in which Cellarius was concerned not only with the interests of the VOC, but also with private trade. The trading town of Cranganoor was ideally suited to trade with native and foreign merchants. Cellarius maintained trade contacts with merchants from his birthplace Ulm, the Netherlands, London and Bombay. He became influential not only as a merchant dealing in such things as clothing, prints, atlases and products from Malabar, but also as a scholar. He had a large library which, in addition to many atlases, contained works by Shakespeare, Voltaire and Rousseau. Dictionaries, novels, books on navigation, but also on history and works of Newton were in his cupboard, probably together with his own work that appeared in 1781: “Aantekeningen over de Spraak, Weetenschappen en Kunsten der Mallabaaren” and the “Cellarius Lexicon Latinum”.[ii] [iii] He was described as "a man of language, reading and passion for good science".[iv] On 17 November 1786, at his repeated request, he was dismissed as chief merchant and bought a house on the Rozenstraat in Kochi for 3,700 reales from VOC servant Jacobus Eversdijck. He moved into the house with his family and ten enslaved people.[v]  First Page “Aantekeningen over de spraak, wetenschappen en kunsten der Mallabaaren”

First Page “Aantekeningen over de spraak, wetenschappen en kunsten der Mallabaaren”

The way back to Europe was still open for Johan Cellarius and his family. Cellarius now owned a country house in Ulm and by marrying a daughter of Johan Daimichen she and her brothers and sisters, the first generation descendants of a European father and a mestee[vi] mother, were still seen as European. The erosion of the power of the VOC, the acquired possessions and the family network made many VOC servants decide to stay despite the expected domination of the English in the area. So was Johan Adam Cellarius. Despite his different interests, he became a prosecutor in Kochi for a few more years. He did take his precautions, for example, he sent his sons Johan Jacob and Johan Adam to Ulm to study there and to settle there permanently. He also decided to stipulate in his will that after his death his daughter should at the earliest opportunity, accompanied, go to Ulm and there "be delivered to the bosom of her paternal family".[vii]

In October 1790, Cellarius, together with Willem van Haaften, had the honor of welcoming the new king of Cochin. The ceremony with flag and cannon shots was described in advance: “The new king of Koetsien comes for the first time to his palace in Koetsien. Cellarius and van Haeften will go to the palace in a carriage to welcome him on behalf of Van Angelbeek and to ask when it is convenient for the king to receive Van Angelbeek. As soon as the Orangbai Van Tripontare comes in sight, the flag will be raised and will continue to blow all day. When His Highness gets close to the palace, he will be saluted from the fortress with 21 cannon shots. At 9 o'clock a detachment of 50-headed Grenadiers with two officers will march from the parade ground to the palace, forming a ridge from the river bank into the palace courtyard and saluting the king, presenting the rifle and the striking the march with banner and spontoon, after which the same forms in the courtyard with the front to the palace or to the place where the king is to stay, and then gives three general salvos with a cannon shot between them, on which neither 18 cannon shots and so 21 will be done in its entirety from the field pieces that will be seconded with the necessary artillerymen until the end, also early in the morning.”[viii]

On October 20, 1795, Cellarius was taken prisoner of war by the British. He remained a prisoner until his death on 15 June 1796. The inventory of his possessions that was drawn up at that time shows how great Cellarius's wealth had been. His daughter Helena was heiress to all his possessions in Kochi and continued to live in the house on Rozenstraat. Despite her father's wish that she would go to Germany, she continued to live in Kochi, probably forced by the English occupation. Francois Joseph von Wrede, Cellarius' brother-in-law, was among other things in charge of the funeral ceremony and executor of the will. Due to the public sale of part of his estate, which took 8 days, we know what Cellarius' library looked like, but also the layout of his house and that he owned a palanquin. Also that he owned a chariot with two horses and wore silk trousers. His wife could adorn her ears with gold earrings, decorated with 108 diamonds. His brother-in-law Frans Joseph bought two pairs for more than 900 rupiah. The cost of making his grave can be deduced from the bill of his funeral. The mason for the bricklaying of the grave received 6 rupya, the purchase of the 'blue' stone on the grave cost 3 rupya, cutting the letters 25 rupya and the fee to the scriba to attend the carving of the letters 6 rupiah.

It is striking, however, that no 'blue' stone, presumably a kind of lime stone, can be found on the grave monument. It could be hidden under the layer of plaster, but possibly it refers to the text stone, which, according to the funeral bill, cost 3 rupiah and would therefore not have been that large. The question is whether the tombstone is original. The design of the monument does not appear original. The Latin text on the stone reads: Piis manibus / J.A. CellariiUlmensis / Obiit 15 Junii 1796. In translation: Devote to the devout soul of / J.A. Cellarius from Ulm / died 15 June;1796.]

His daughter adapted to the new circumstances among the English and married the English Hugh Masseij Fitzgerald in 1801. Everything indicates that the wife of Cellarius was still alive on November 7, 1795, when her mother died,[ix] but when her husband died, only their children are still mentioned, so she must also have died between November 7, 1795 and July 15, 1796. The three children were then allowed to divide 81,849 rupya.

Notes

[i] Albrecht Weyermann, Nachrichten von Gelehrten, Künstlern und andern merkwürdigen Personen aus Ulm (1798); NA 1.04.02.12506 scan 0036

[ii] Reissue Nabu Press September 2011

[iii] NA 1.11.06.11.1557

[iv] NA 1.04.02.3619 scan 132

[v] NA 1.04.02.7608 scan 910

[vi] In India mestiços are persons born of a European, often Spanish or Portuguese, father and an Indian mother or vice versa. Sometimes they are also known as ‘mestiças’ In a broader sense, anyone of mixed ethnic origin is sometimes referred to as mestiços. In English they are called mestees.

[vii] NA 1.11.06.11.1557

[viii] NA 1.11.06.11.1359 scan 264

[ix] NA 1.11.06.11.1461

Singh, A.: Fort Cochin in Kerala 1750-1830 : the social condition of a Dutch community in an Indian milieu

Doop en trouwboek Cochin, Gens Nostra 1992

- Last updated on .