Case 1: Peneleh

A little history

A true expansion of the Dutch East Indies took place in the nineteenth century. Railways and modern technology made it possible to clear the interior, rocks and mountains were made small with pneumatic hammers for tunnels and other structures. Cities such as the former Batavia and Surabaya grew into world cities with large ports. This attracted thousands of Dutch people, but also others from all over the world.

Previously large enough cemeteries and small churchyards could not cope with the growing number of dead, and a new cemetery was soon needed. In 1846, the municipality of Surabaya opened the Peneleh cemetery, then still far outside the city. Peneleh was a so-called European cemetery where Protestants, Roman Catholics, Jews, but also native and Chinese Christians were buried. The fact that not a delineated piece was laid out for every faith reflects the true general character of this burial site. All kinds of nationalities are also mixed up, so that the visitor can find not only Dutch texts, but also Japanese or Armenian texts in addition to German and English texts. Two types of graves were issued at the cemetery: cellar and sand graves.

The cemetery was some 11 acres in size. Probably the site was not put into use at once, but burials started from the center. Tradition has it that there were no trees in the cemetery, making it a suffocating plain that certainly did not invite to visit a grave.

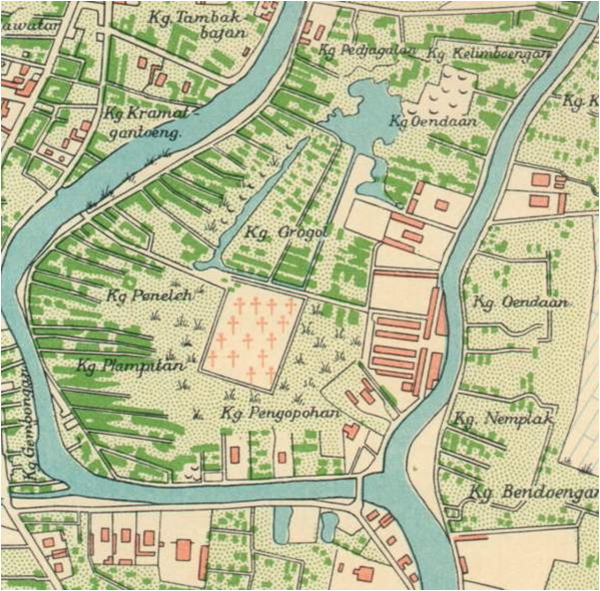

Peneleh on a map of 1866.

Peneleh on a map of 1866.

Special trenches were dug for the purpose of draining excess water that could fall in large quantities during the rainy season. The ditches drained to the south side of the cemetery. Some older maps clearly show that the cemetery is located in a swampy area, surrounded on three sides by rivers. On one map there is a ditch or something similar around the cemetery, while on the other map there is no question of it. The older maps do not yet show any buildings around the cemetery, but in the years around the First World War the cemetery became almost completely enclosed by kampongs. At the time, the number of European residents of Surabaya had increased significantly. While in 1857 the city still had some 7,500 Europeans and others assimilated (often Christian Chinese or natives married to Europeans), by 1920 there were already almost 18,000.

After almost a century of intensive use, the burials at Peneleh came to a rather abrupt end after Indonesia's independence. Meanwhile, a new cemetery had already been built, Kembang Kuning. From the sixties of the twentieth century Peneleh was more or less outlawed and residents of the kampong began to use the site more and more as they saw fit. Occasionally, a grave was opened for a transfer to Kembang Kuning, but otherwise nature had free rein. Ultimately, it was not nature that was responsible for the current situation. The current damage picture is too explicit for that. Large holes in the cellars have been deliberately made to gain access to the contents. Those contents, coffins, corpses and other items there were probably all looted. The holes were filled with waste, the bricks were used to build walls for small extensions to the surrounding houses. Slabs will have found their way here and there as paving, although no direct indications of this can be found in the surrounding kampong.

How to proceed with Peneleh?

In 1998, the Municipality of Surabaya decided to classify the cemetery as an important historical monument. But the problem is that the municipality has no budget to do anything about the maintenance of the cemetery. In recent years, a number of people have been appointed from the cemetery management to do some maintenance. This mainly means that the part where there are now trees is kept free of leaves. Due to the climate, there is not one period in which the leaves fall, but that continues all year round. Small piles of leaves are always burned on the spot by the maintenance crew. Occasionally a grave is renovated, sometimes by next of kin. However, the small amount of maintenance cannot improve the maintenance condition. For the time being nothing is being done about the funerary monuments.

The fact that the municipality of Surabaya is aware of the historical heritage that forms Peneleh, led in 2011 to a collaboration with the Dutch Cultural Heritage Agency (RCE) and the Technical University of Surabaya (Institut Teknologie Sepuluh Nopember). In October 2011 they organized a workshop together. In five days, the possibilities for the cemetery were examined with architecture students from the university, employees of the municipality and a few experts from the Netherlands. This showed that the pressure from the kampong for things like recreation, market and other activities was very great. In addition, the cemetery is used as the shortest way to the other side. The workshop worked towards a certain description and appreciation of the cemetery, but also looked at the design possibilities of the space. The results of the workshop were presented in December 2011. At the end of 2012, the workshop was followed up in a further elaboration of the plans. It became clear that many graves might be cleared. Incidentally, that would not be the first time, because the records show that many graves have been cleared in the past.

One of the recommendations from the workshops was, among other things, to set up a foundation from the Netherlands that could (partly) finance the preservation of Peneleh. A small management organization would then have to be set up in Surabaya that would manage the cemetery and restore a number of grave monuments. But it has still not come to that. Anyone who looks at aerial photos of the cemetery can see the same picture over the past ten years.

Situation update

...

- Last updated on .